Silence. At last! After hours of nearly relentless droning, quiet. For the second time in a week, a raucous engine had shut down; the first time came prematurely after not quite 36 hours. Silence then brought long faces. This second noisy run went on for 96 before the noise stilled. Then came the applause. And cheering. And then the sounds of champagne bottles and beer bottles popping their tops.

This thing had started the way things like this usually do, with a couple of guys nursing their beers, commiserating with each other over their lot in life. They were in the middle of a long successful season. But it was a season. It had an end point. The general theme was “What’s to become of us?”

It was a late summer evening in 1967. The two guys, Rico Steinemann and Dieter Spoerry shared ownership of a Porsche Typ 906 Carrera 6 Long Tail, bright red with a wide center white stripe representing the national colors of their native Switzerland. They had raced their car and other automobiles for different owners throughout the year. In a Ferrari 275 GTB/Competizione they had run the 24 Hours of Le Mans on June 10 and 11 and had won the under five-liter GT class. But when the fall and winter came and racing stopped, what was to become of them? They were long distance runners but they weren’t especially winter rally competitors.

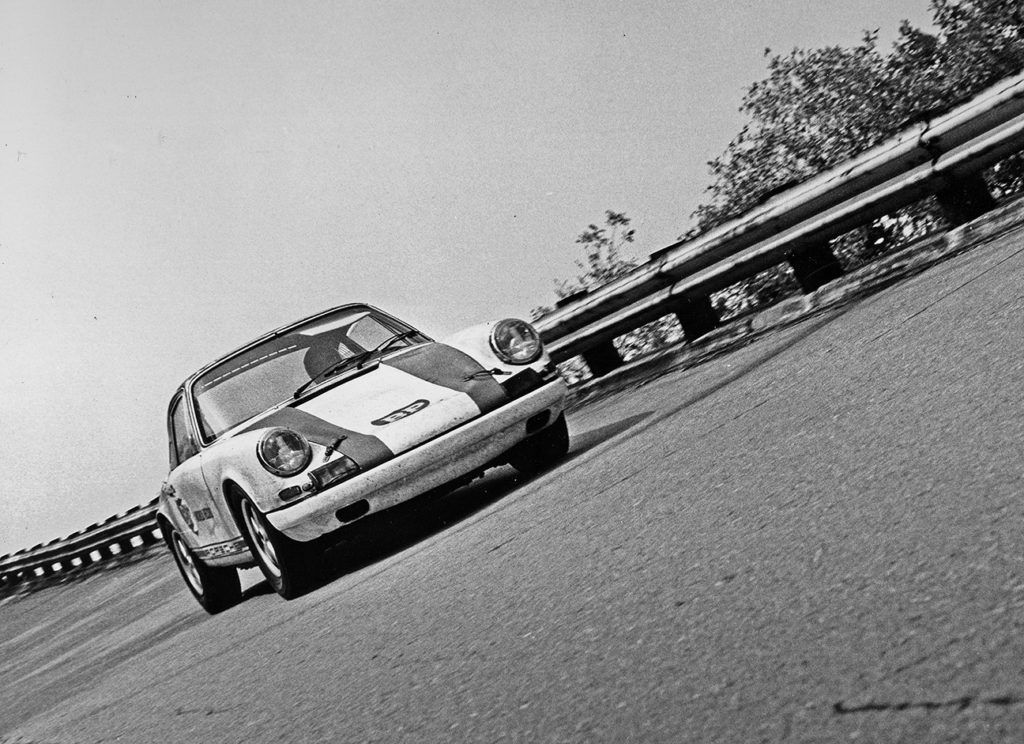

An idea came to them. Porsche had held several long distance world records for some time. But in 1966, Toyota had captured some on Japan’s new circuit at Fujiyama – averaging 128.0 miles per hour while Ford had set others averaging 111.8 miles per hour on the banked track in Daytona, Florida. The gearing on their Carrera 6 gave them a top speed of 167.8 miles per hour so new records seamed feasible. They settled on running at Monza in northern Italy. The Milan Auto Club had employed 3,500 workers to built the circuit in 1922 of poured concrete. But over decades, the earth beneath some sections of the 2.64-mile oval had settled causing some pavement breaks, and 45 years of weather had scoured its once smooth 30-degree surface. Still, in 1958 an American racecar set an all-time lap record of 176.06 miles per hour.

Spoerry and Steinemann got FIA approval, rented the Italian track, lined up Swiss BP and Firestone as sponsors, and enticed fellow Swiss racers Charles Vogele and Jo Siffert to join the effort. Porsche and Ferdinand Piëch came on board, supporting these successful racers with personnel and technical assistance. For the run, they fitted a regular 906 tail to their car, opting for stability over top speed.

Their attempt started at noon Saturday, October 28. They achieved their first records, for 1,000 kilometers, 1,000 miles, and 2,000 kilometers, on the first evening. They were averaging 141.0 miles per hour. But then the Monza banking started taking its toll. By 10 p.m. Sunday, the 906 had broken and replaced suspension parts three times. Rules required the car to carry all the spares and replacement parts anticipated for the duration inside the car. With no more appropriate spares on board and the chassis damage severe, their run was over.

There was no time to wonder what was to become of them. FIA regulations allowed them 48 hours to restart the run without penalty. Steinemann called Ferdinand Piëch at his home and explained the situation. Piëch thought a 911R might be capable but he needed to make some calculations. An hour later, Piëch let them know the car was too slow. He called back moments later and said his calculations might have been off. It was nearly midnight. Piëch promised more information in the early morning. Because the 906 had set some records, no one left. FIA officials had to make a thorough inspection of the car to certify the results. Meanwhile, Siffert and the three drivers met with BP and Firestone officials. Siffert had driven a 911R prototype already and he knew it was fast and strong enough.

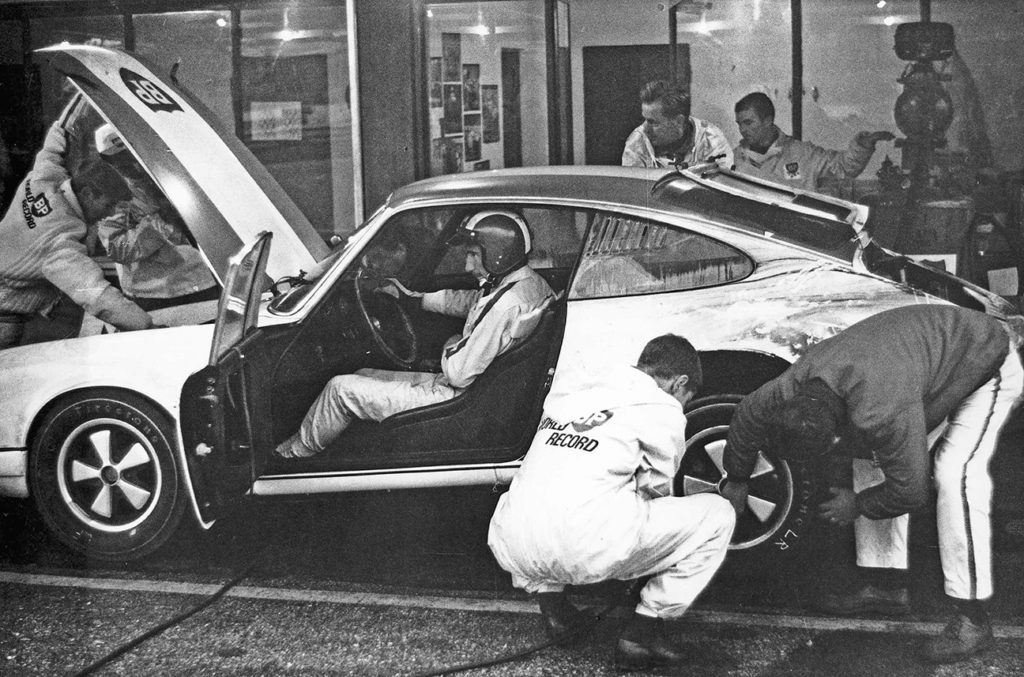

At Zuffenhausen Monday morning, Piëch gathered Helmuth Bott, engine chief Paul Hensler, drive train head Richard Hetmann, Peter Falk from racing, and experimental department boss Albert Jünginger. They and their staffs quickly got to work revising and preparing a team of the all white 911R coupes for this trial. By luck of the draw, 911R-001, the first of the 20 production versions, was designated as the record challenger. Knowing that any parts it might need over the run had to be carried on board, and certain that Italian customs would painstakingly examine and catalog every spare part, causing an unimaginable delay at the border, Jünginger and Porsche’s chief mechanic, Heinz Baüerle left for Monza in a back up car to be dismantled for its parts once it got there. Hensler secured an engine, a twin-plug Typ 906 of the kind typically installed in the 911Rs. Hetmann modified the five-speed transmission, guessing so many hours nearly flat out in fifth might wear out the gear. He made 4th and 5th essentially identical. Once this work was complete, Hensler and Hetmann departed as well. But just before they left they discovered Hensler’s engine had recently completed a 100-hour bench test. Mechanics then dismantled, inspected, and reassembled it, but no one knew how carefully or if they fitted new parts.

The cars, with their pure racing engines, were too loud for the noise-conscious Swiss to allow through their country. The first parts-donor car was turned away at the border and it and the record run car hours behind it had to detour through France to reach Italy. A recently discovered photo shows three of the 911Rs in the Monza pits so an additional car was dispatched, either to serve as 001’s back up or to provide more spare parts. Car 001 reached Monza early Tuesday morning.

As the clock ticked toward the 10 pm Tuesday restart time, another problem became clear. Firestone had provided dozens of sets of tires for the 906 yet these were not correct sizes for the R. Firestone had some on hand but they had to fly in enough for the rest of the trial.

Late fall weather in northern Italy brings rain and fog and both of these plagued the run. Fog reduced visibility sometimes to 20 or 30 meters. Rain flooded the back straight creating a lake the drivers learned to blast through at 125 miles per hour to stay on pace. Rain and the splashing from the lake played havoc with electronics, leading mechanics to replace all 12 spark plugs on the third night. By this time, 001 had covered more than 10,000 miles, nearly 16,100 kilometers. Each of the racers drove for 90 minutes, and then had four and a half hours off, never time enough for a deep sleep.

As with the 906, front struts failed and mechanics replaced them with spares in the car. Hetmann’s premonition on fifth gear came true on the four day. Having run 24 hours a day between 6,500 and 7,000 rpm, covering more than 20,000 kilometers, the gear failed. The drivers used fourth and saved the attempt.

At 10 p.m., Saturday, November 4, 1967 – 50 years ago on the first Saturday in this November – R-001 pulled into the pits for the last time. It had established 16 new world and international speed records including 20,000 kilometers at 130.77 miles per hour and 96 hours – at the same speed – to cover 12,505.38 miles. At Le Mans five months earlier, the winner in the under-two liter GT class, a 911S, covered 2,583.8 miles. At Monza, R-001 averaged 3,126.35 miles every 24 hours over four days. Firestone set a record of its own for tire consumption: 90 tires in 96 hours.

The 911R-001 has lived in southern California for more than a decade and as the 50th anniversary of its signal accomplishment has passed, it has completed a multi-year meticulous restoration down to rebuilding the engine with the correct titanium connecting rods. As it starts its 51st year the car is beginning to appear in public liveried in the red stripes the four Swiss racers hurriedly applied to the car before their long drive.