(13 October 1921 – 28 September 2011)

“Larry!” The voice was strong and gravelly. It had a soft accent that assembled elements of Czech, Italian, Spanish, German and English in a gentle, aristocratic structure, recognizable from a recent telephone conversation. Jaroslov Juhan’s hand went up in the crowd. “How good to meet you after all these years.”

This meeting was not coincidental. During a brief telephone conversation a few weeks earlier we discovered we would both be in Piazza della Vittoria for the Mille Miglia Storica tech inspection. I flew in from Detroit and “Jerry” drove down from Geneva. We had been friends through correspondence and a few brief telephone conversations for nearly 30 years, though we had lost contact for about 20 of them. We walked and chatted along the line of cars leaving the tech dock and winding through the alley of Via XXIV Maggio up to Piazza della Loggia where all the teams and cars were gathering to apply roundels and pack their cockpits before dinner and the long evening starting ritual of the historic adventure. We settled at a small table to share a lunch, admire the eclectic gathering of our favorite machinery and talk of Porsches – and life. He suggested we could spend the evening near the starting ramp on Viale Venezia. He regretted missing the opportunity to race in the Mille Miglia, but there were many stories of adventures in Central America.

To Guatemala

How did a young Czech make his way to Guatemala in the difficult postwar years? The long-published stories and the one he told now differ in detail. As a young racer and enthusiast he had opened a small business importing and servicing Italian vehicles in Prague. Established as an energetic entrepreneur with the Fiat marketing staff, he was offered the opportunity to be part of a large Fiat contract in Central America. It seems Guatemala was planning a trans-national truck road to compete for the Pacific-Atlantic commerce creating wealth in Panama. They contracted 1,500 of Fiat’s new tractors for the project and that required a reliable management team – and an advance-party of planners. Juhan arrived there before his 30th birthday in 1951. He had assembled some resources of his own and the Fiat contract made him comfortable and even more entrepreneurial.

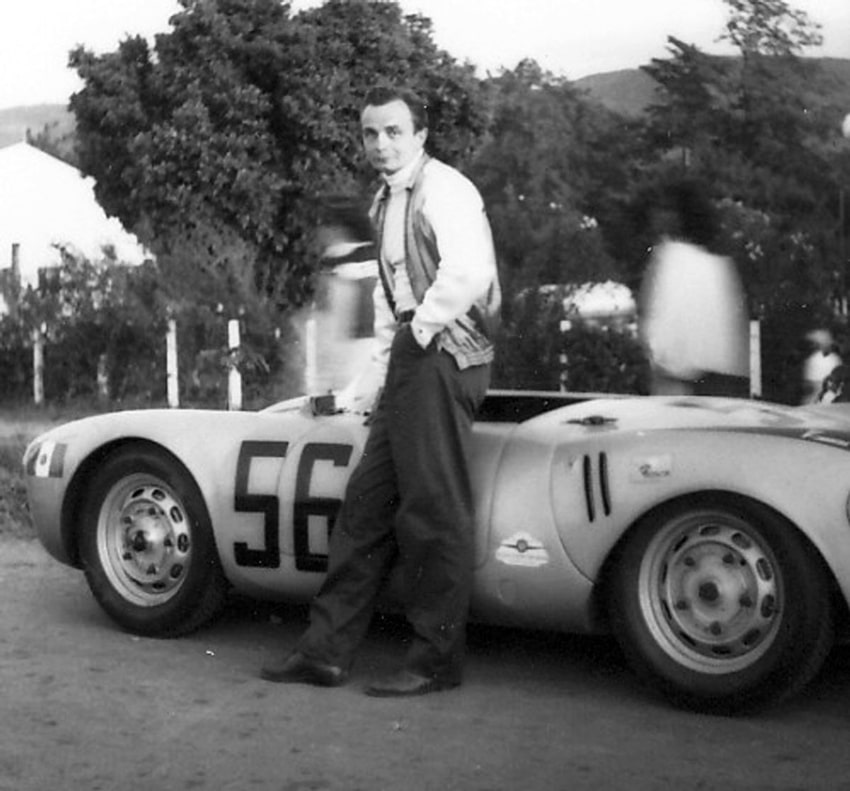

While making himself familiar with the Guatemalan landscape, he discovered an ardent racing fraternity. He quickly established a small shop to import and service European sports cars while waiting for his tractors to arrive. He soon included distribution of Porsche for Central America in his business and helped found Federación Deportiva Auto e Moto of Guatemala; it was recognized by the FIA in Paris. The grand highway project was cancelled and the Fiat contract with Guatemala came to an end – along with his own employment. But his business continued growing.

After Juhan added Porsche to his imported sports car catalog, he took delivery of a new 356 1500 Super for himself. It gave him his first victory in Guatemala’s Carrera de Pacifico, and with it, two additional Porsche sales. His order included the first two Porsche Typ 550 Spyders in a purchase arranged with Ferry Porsche. Juhan was to race them a few times in Central and South America as marketing for additional sales, and pay Porsche when they were eventually sold.

First 550s arrive

Before crossing the Atlantic, the prototype (550-01) won its class at the Eifelrennen in May of 1953 driven by Helm Glöckler, whose cousin Walter’s Volkswagen special had inspired the new Porsche racecar. Helm and Hans Hermann took a class win at Le Mans with 01, supported by Richard von Frankenberg and Paul Frère in 02; Porsche fitted both cars with aerodynamic roofs for the fast Le Mans circuit. Both 550-01 and 02 raced at AVUS, in the Freiburg-Schauinsland Hillclimb, and at the German Grand Prix at the Nürburgring before being completely overhauled before shipment to the new distributor in Guatemala.

At the request of Prince Alfonso von Hohenlohe, and with the financial and material aid of Fletcher Aviation of Pasadena, CA, Porsche entered 550-03 and 04 in the 1953 Carrera Panamericana “Mexico” in November of that year. Porsche wanted Huschke von Hanstein, Hans Herrmann, and Karl Kling to drive the new 550 RS roadsters, with technical support from factory mechanics Willi and Werner Enz (unrelated). Juhan was to be responsible for his own 550s, though the factory technicians were available if needed. Von Hohenlohe’s VW/Porsche facility in Mexico City was headquarters during the weeks of route reconnaissance, but before that began, Fletcher wanted the cars to race in the U.S.

Upon arrival in New York Karl Kling was immediately arrested and accused of being a Nazi general. Von Hanstein (who had worn an SS insignia on his racing coveralls in 1940) stepped in and explained that Herr Kling was no general, nor even a Nazi. He just was an internationally recognized racing driver.

The two cars failed at the Turner Air Force Base SCCA event in Albany, GA; it was a fortunate test before Mexico – but not enough. Both of the Porsche/Fletcher cars were out again by the second leg of La Carrera. Juhan then led the “Small Sports Car” category (using Mexican Goodrich Excadis tires inflated to 56 psi to survive the abrasive road surface) right to the last leg, when 550-01 failed with a broken distributor drive.

“But it was not over for me.” Juhan remembered, “I was in the middle of the desert with $10 in my pocket. I had to get myself and the car back to Mexico City. A couple of Mexican truckers stopped to help.” He explained his dilemma after which they loaded the car in the truck, collected the $10, and drove the unlucky racer and his sports car the 2,000 kilometers to von Hohenlohe’s shop. José Herrarte of Guatemala brought 02 into Juarez for the class win. Finally 550-01 (pushrod engine) and 04, 05, and 06, each with 4-cam engines, were there at the finish. Juhan (05) finished second in class behind Hans Herrmann (04) and they were third and fourth overall. Von Hanstein was happy. He paid for the post-race celebration.

Back to Europe

In 1961, with Central America smoldering toward a conflagration, Juhan, a life-long ex-pat sportsman/businessman, left his adopted home and Guatemalan family to resettle in Geneva, Switzerland, where most of his success was safely stored. Well known in the racing world and now recognized as a knowledgeable intermediary with the mysterious world of Swiss banking, he continued to do what he loved — spend time with old friends and sequester new resources. A few other well-known auto industry personalities were “colleagues” in that enterprise during the next few decades. Many were guests in his villa in the south of France.

I left Road & Track to join Automobile magazine in Ann Arbor, Michigan and lost touch with Juhan. He saw my story about driving Ferrari 250 Testa Rossa 0754 for its long-time owner, David Love, published in Graham Gauld’s Historic Racing magazine and he went in search of his old friend – both his old friends – the owner and the car. He had purchased 0754 new at the Ferrari factory in 1958 for a Le Mans entry with François Picard as “Equipe Los Amigos,” painted light blue, the official Guatemalan livery, and wearing race number 20.

In a drenching rain six hours from the start, his co-driver made contact with Jay Chamberlain’s Lotus under the Dunlop bridge and the impact damaged the #20 Ferrari Testa Rossa beyond continuing. The car was returned to the factory for repairs after the race and repainted red at that time. Juhan decided it was his time to retire and he shipped the car to the dealership of an old Porsche friend in Southern California, Vasek Polak. (This was the Testa Rossa that Jack McAfee raced before it was sold.) Jerry joked with David Love about “Vasek and profit” when they spent the Monterey weekend with the never-retired Testa Rossa a few years ago. (When Love was finally overtaken by his Parkinson’s disease, 0754 found a new home and it now is in gloriously new condition.)

Czech Republic

There were few failures in Jerry Juhan’s life, but his retirement was certainly one of them. Because he didn’t stop working. During 1996, in an effort to give something back to his newly revived homeland, he became a financial partner in Bohemo Sport a volny cas a.s. (Sport and Leisure LTD). His goal was to restore the old Masaryk Circuit at Brno in center of the new Czech Republic and promote a vintage racing series. His first was a 2000-kilometer race to the A.C.O. Le Mans regulations shortly after the Sarthe event. He dreamed of an unlimited CanAm event to reintroduce the circuit. I furnished a list of owners that he could likely persuade to bring a show. Now, the Brno Circuit runs a full schedule of international events including the Czech Moto Grand Prix, Masaryk Racing Days, and a vintage Formula One date among a host of others. Jerry’s dream of bringing racing back to the Czech Republic thrives.

The circle closed. Juhan died during September of 2011. A beautiful scale model of 0754 in its Guatemala light blue Le Mans livery (a gift from its proud original owner) occupied a place of honor in David’s office until he too passed away a couple of years later. An extra bundle of correspondence between Juhan, Love, and me is safe in a file.