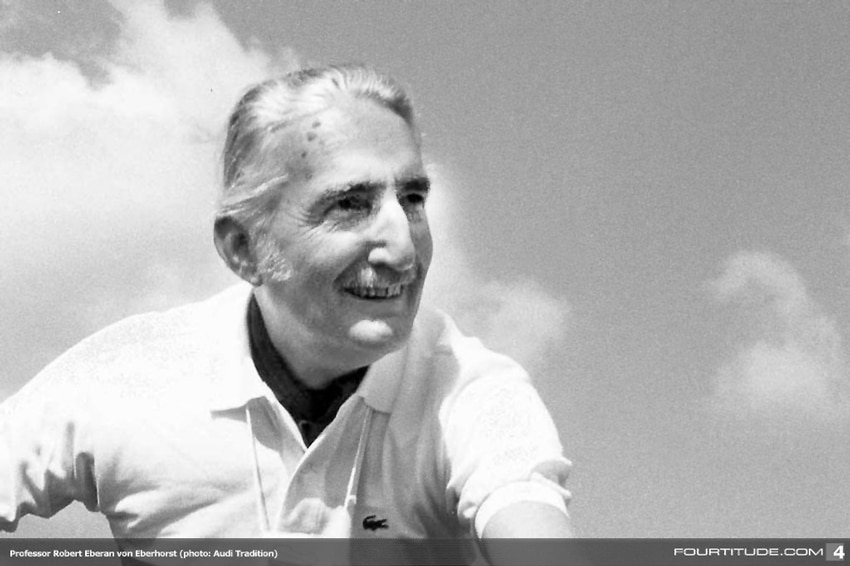

Robert Eberan-Eberhorst was a disciplined scientist who expected that of his colleagues. That included Ferdinand Porsche.

Professor Robert Eberan-Eberhorst (23 October 1902 – 14 March 1982), was born Robert Eberan von Eberhorst, the son of Alexander Eberan von Eberhorst, a high-level administrator in the Austrian postal hierarchy who became a distinguished Austro-Hungarian Vice-Admiral during WWI; a clear line of nobility, but the “von Eberhorst” was lost when Austrian nobility was abolished in 1919 and should never be used post that date – though no one seems to care about its later authenticity.

Early Days

After mastering the presence of an aristocrat and the discipline of a military household, Robert Eberan-Eberhorst completed primary school and began his technical studies at the Höhere Technische Bundeslehranstalt Wien (Higher Technical School of Vienna). In search of access to work experience, he apprenticed at Puch Motorcycles in Graz at the age of 20. In 1924 he was invited to join Elite Werke, a manufacturer developing a line of fine quality automobiles at Brand-Erbisdorf in Saxony, southwest of Dresden. Now inspired, Eberhorst returned to Vienna Technical University where he earned an engineering master’s degree in 1927 – while recording a series of motorcycle hill climb victories, beginning his experimentation in air-fuel mixtures and falling in love with the multiple challenges of motorsport. Later that year he joined the Institute for Automotive Engineering at Dresden Technical University (famous for its Institute of Engineering Measurement and Interchangeable Manufacture) as a research assistant and PhD candidate where critical measurement and analysis were vital to their program.

He returned to Vienna with his new credential, but found only employment as an independent driving instructor for two years before he was offered a position of adjunct professor at his alma mater in Dresden. His primary focus for the following five years was the study of mass balance, the balance of rotating bodies, and their affect on chassis vibration.

Auto Union Glories

Five years later, in 1933, the Nazi party fired all professors and restructured TUDresden; Dr. Ferdinand Porsche persuaded Dr. Eberan-Eberhorst to join his consulting team, commissioned to create a new grand prix car for the recently formed Auto Union. The new group was formed of Horch, Audi, Wanderer and DKW. Eberhorst’s position was development engineer within the Auto Union racing department at the Horch works in Zwickau, where he was responsible for turning Chief Engineer Porsche’s ideas into physical reality. His early individual contributions included developing effective measurement of all systems including the driver. He also created side skirts on the aerodynamic bodywork along the belly of the record-breaking streamliner, one of the earliest experiments with ground effect down force to have been applied to a car.

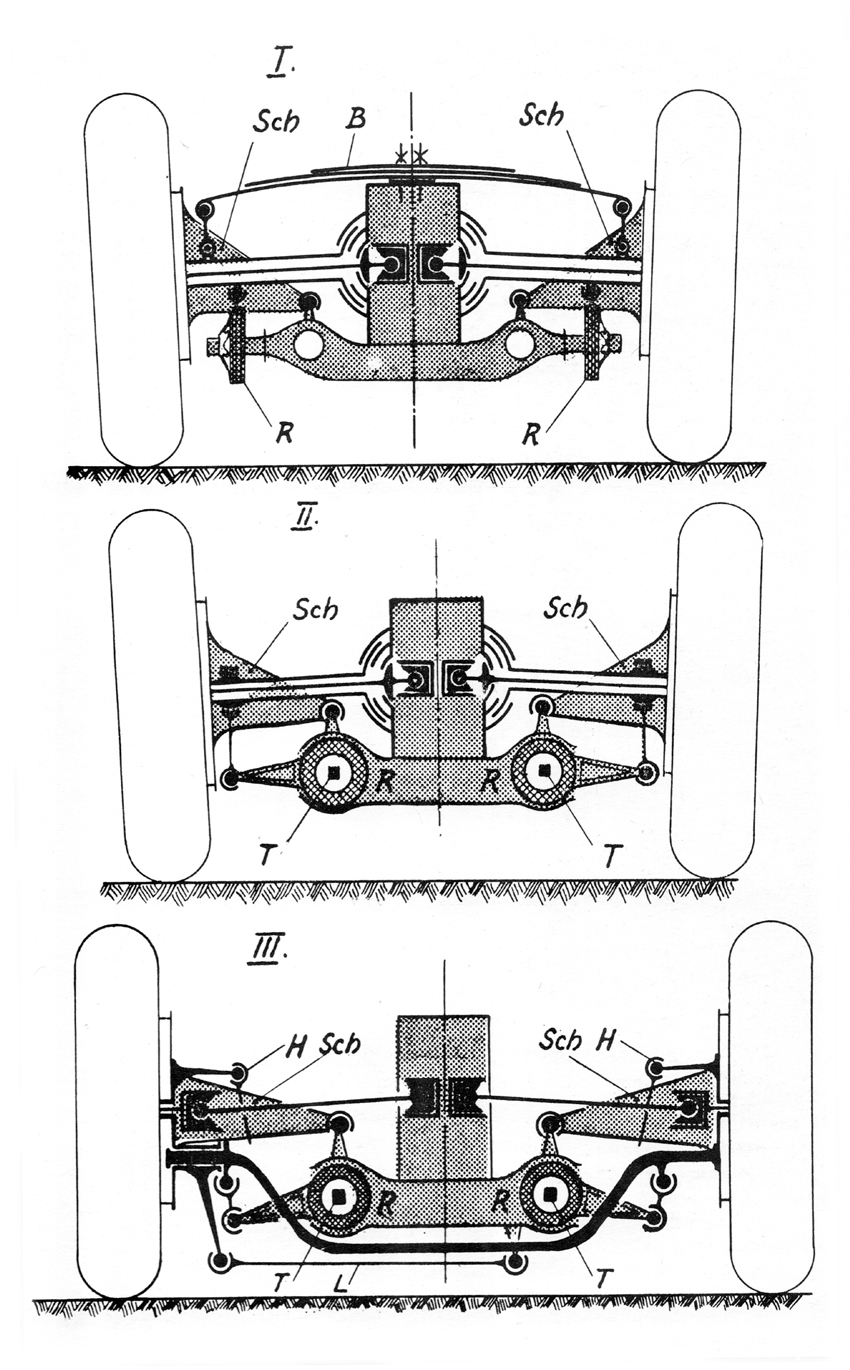

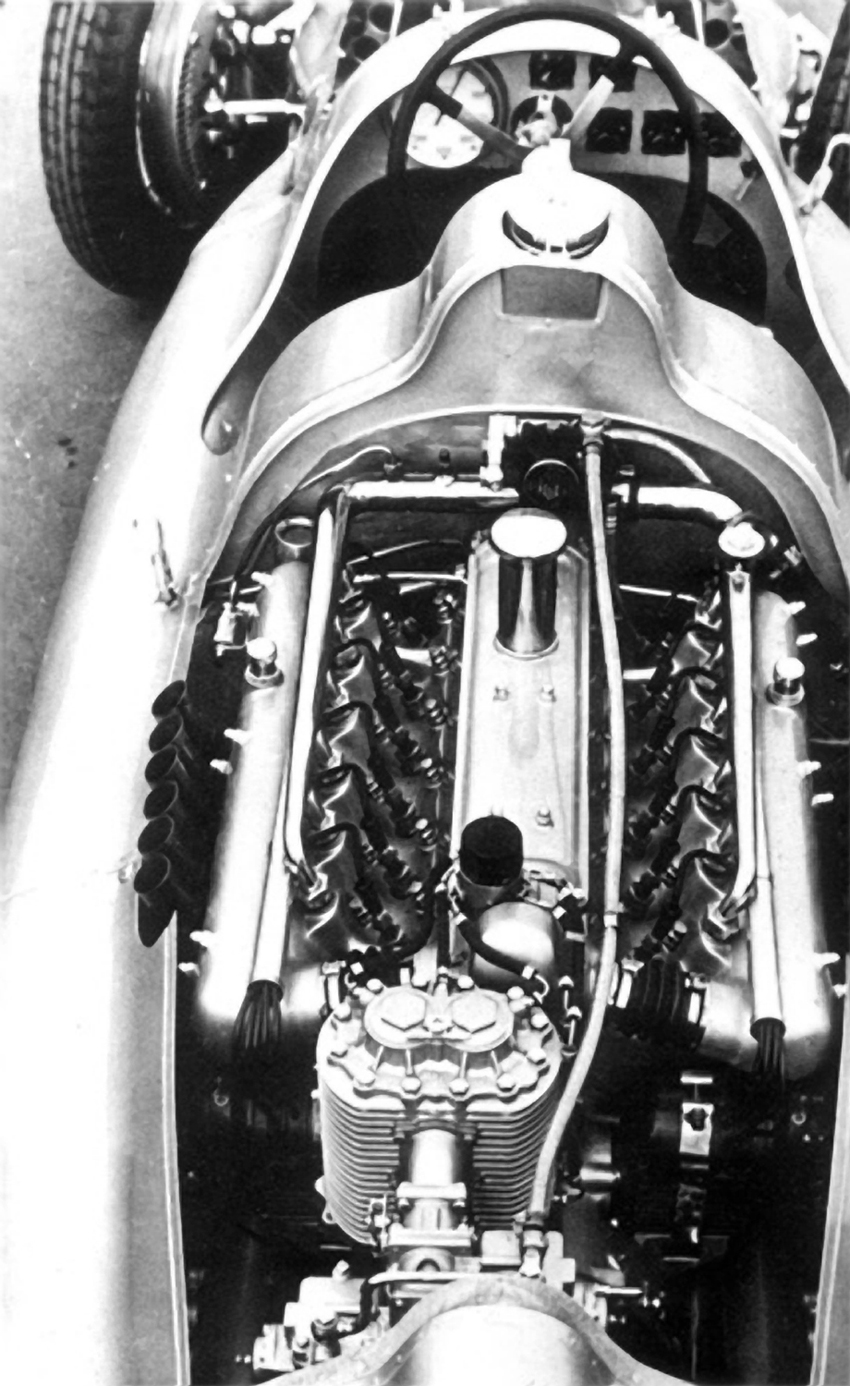

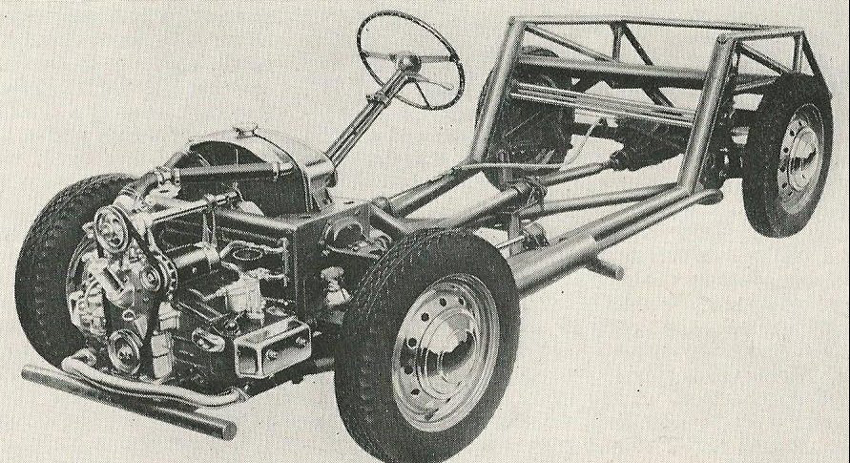

When Porsche left Auto Union in 1938 to complete his work on the national leader’s people’s car, Dr. Eberan-Eberhorst was promoted to Design Director of the new 3-liter Type D, his first complete car design. The new chassis retained the parallel large-diameter tubes for structure, but placed the driver back near the center of the car. This was done by reducing the engine by two cylinders and removing the fuel tank that had been fitted between the driver and the engine in Porsche’s previous designs, forcing the driver far forward. He replaced the fuel volume with a pair of side tanks that doubled as an aerodynamic element between the wheels, a constant in the doctor’s vision. Perhaps the most important chassis update eliminated the challenging swing-axles and replaced them with a De Dion tube dead axle. While it did not permit the tires to change camber under load, it did permit a fixed camber angle that could be adjustable by replacing the De Dion tube with different stub-axle angles at its ends – offering a much more predictable dynamic.

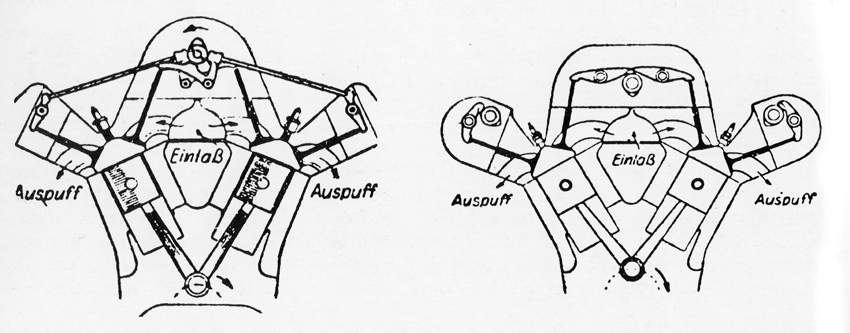

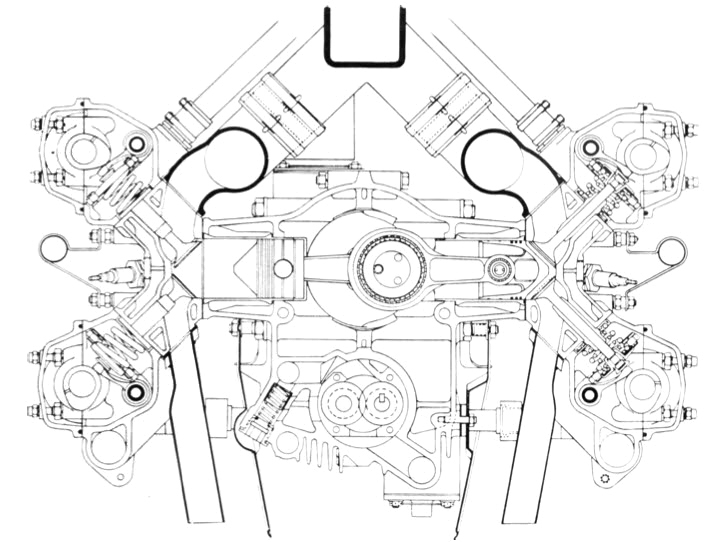

Eberan-Eberhorst’s supercharged 2,984.9 cc V-12 followed Dr. Porsche’s general V-16 layout, but early 4,358cc (Type A), 4,951.3cc (Type B) and 6,002.2cc (Type C) versions used a single camshaft mounted high between the heads with intakes operated by rockers on the cam, while exhaust valves, on the bottom-side of the heads, were operated by cam-follower-rockers, long pushrods and a second set of rockers at the valves. Eberan-Eberhorst retained the high central cam with rockers for the intake valves, but gave each head an additional camshaft to operate the exhaust valves by their own rockers. The 3-liter engine could develop 480 hp, only 40 less than the 6-liter V-16, but it was not enough to stay with the 3-liter V-12 development of Mercedes.

Eberan-Eberhorst was heavily involved in the initial testing of each new racing car, developing on-board recording instruments to plot parameters such as car speed, engine speed, timing of gear changes and braking points from a time-distance calculation – the chief engineer was also known to be standing track-side to observe with a critical eye and stop watches. To his driving team it seemed to put the performance-driven engineer inside the cockpit with them. That devotion to critical measurement and analysis would challenge his colleagues throughout his career.

In 1940 Eberan-Eberhorst returned to Technical University Institute in Dresden as a Professor of Combustion Engines and Cars. Near the conclusion of WWII he sent his wife and son south out of Dresden just five days before the Allied forces bombed the university – and the town – virtually out of existence. What remained was in the Soviet occupied sector of defeated Germany. “I stayed on,” the professor wrote, “and eventually the Russians came. One day they ‘invited’ me to go to Russia. I fled that night, leaving all my possessions behind.”

In Italy

In 1947 he had made his way to Turin as a contract engineer. During that early post-war era of unlimited optimism and possibilities, Italian prewar business phenom in both manufacturing and banking – and racing – Piero Dusio, decided to create his own team and build a series of Fiat-based racing cars. Works designer Dante Giacosa began the design before the war, though it was never constructed. After the war Giovonni Savonuzzi, Fiat’s experimental aircraft designer, wanted to move into racing and joined Dusio for 10-times his Fiat salary. Austrian tuner specialist Carlo (nee Karl) Abarth was contracted to develop Fiat’s new 1.5-liter engine and Piero Taruffi came aboard to manage the racing program. When his team’s early success with light cars seduced Dusio to consider Grand Prix competition, Abarth enlisted his friend and schoolmate Ferry Porsche to offer his Gmünd engineering team including Auto Union designer, Robert Eberan-Eberhorst. This project became a view of Porsche’s future when the designers proposed a 1.5-liter flat 12 with four overhead camshafts driven by perpendicular shafts with bevel-gear sets. Abarth and his co-director Rudolf Hruska convinced Dusio to go directly into production with six supercharged 4-wheel drive cars. Costs multiplied and the project occupied the entire Cisitalia facility. Eberhorst insisted on his usual requirements for proper jigs, test-beds and tooling; his view was that engines are better broken on a test-bed with time to reconsider than on racetracks when it’s too late. No one listened. While the purpose of the Cisitalia 360, to raise resources to pay the ransom to extract Dr. Ferdinand Porsche from French prison, was met the car never turned a wheel in anger. Dusio slipped into bankruptcy and the Cisitalia production along with the GP car were moved to Argentina where Juan Perón promised to pay off Dusio’s debt and put Cisitalia into production; step one was achieved, step two was not. The Porsche team and their veteran engineer refocused their energy on the first car planned to wear the family name, project 356.

And then to England

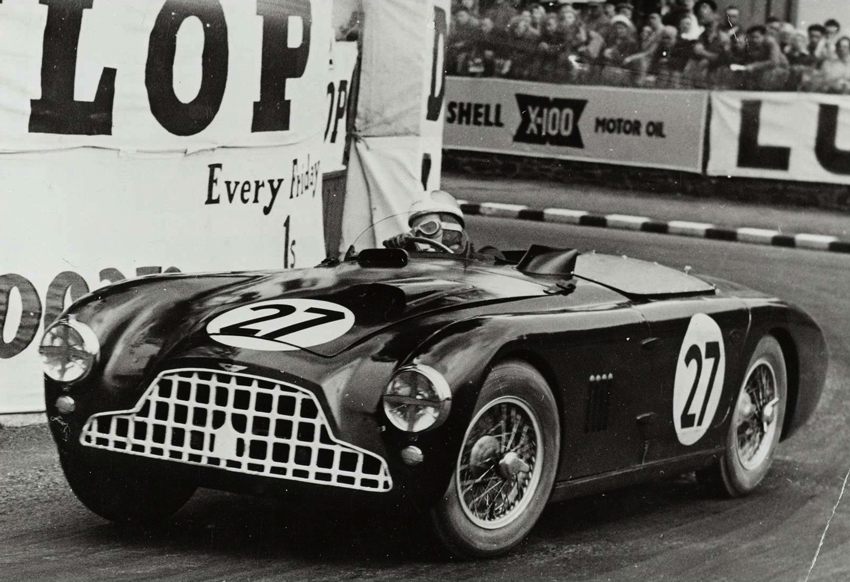

With the encouragement of Laurence Pomeroy, an English journalist and old friend from the pre-war days with Auto Union, Eberan-Eberhorst was convinced to relocate to England to join Leslie Johnson, who had just purchased ERA, and take over the racing development in 1948. For Chris Nixon’s “Racing with the David Brown Aston Martins” he wrote, “I went to Dunstable expecting to find a proper racing plant, but found instead a sort of backyard garage!” Eberhorst wrote that he was “loaned out” to Jowett to assist in a competition chassis. “They had no design tools (in the Yorkshire factory) and I designed the chassis frame by drawing it out in chalk on the shop floor.” His friend Pomeroy intervened again in a contact with David Brown, who had recently purchased both the Aston Martin marque and Lagonda, for whom W. O. Bentley had just completed a 2.6-liter, dohc 6-cylinder engine. He correctly thought it would make his Aston Martin DB2 coupes into racing cars. Once on David Brown’s payroll Eberhorst was asked to assist in the creation of a racing roadster using the new engine. He created a tubular, ladder frame with double trailing arm torsion bar front suspension and De Dion rear axle – it would be called the DB3.

Eberan-Eberhorst wrote: “I left Aston Martin because I was invited to join the board of directors of the newly-formed Auto Union company in 1953. That was a very generous offer, which I found very attractive after the disappointing experiences in England.

“Both my wife and I enjoyed living in England very much and we were sorry to leave. Our son was educated there and we made many good friends at Aston Martin and other places. Although we were returning to our home country, it was a sad farewell.”

Later Years

The Battelle Institute in Frankfurt invited him to join as Head of Mechanical Engineering in 1956 and four years later he took over responsibility for the Combustion Engines and Automotive Engineering Institute at Vienna University. From October 1958 to June 1959 he was also President of the National Sports Commission for Automobile Sport in Germany. In 1965 he retired from the Vienna University, but remained in his favorite city and continued to author technical papers on subjects he thought should be explored.