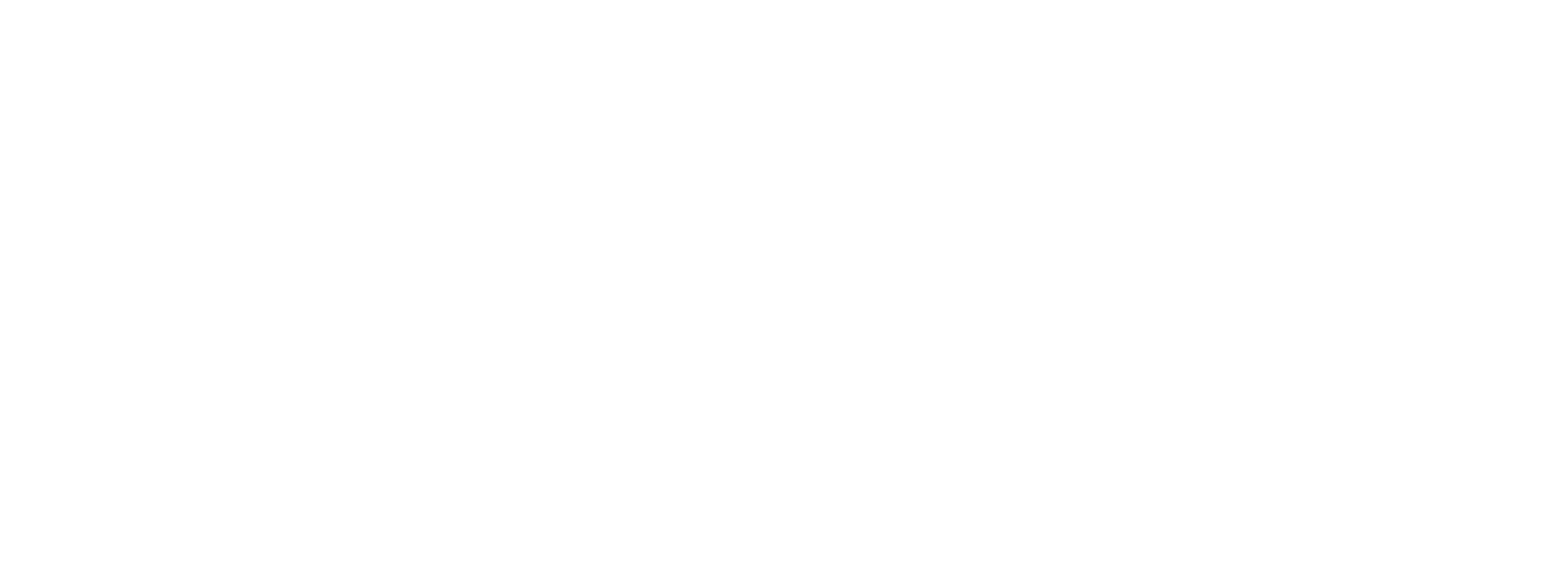

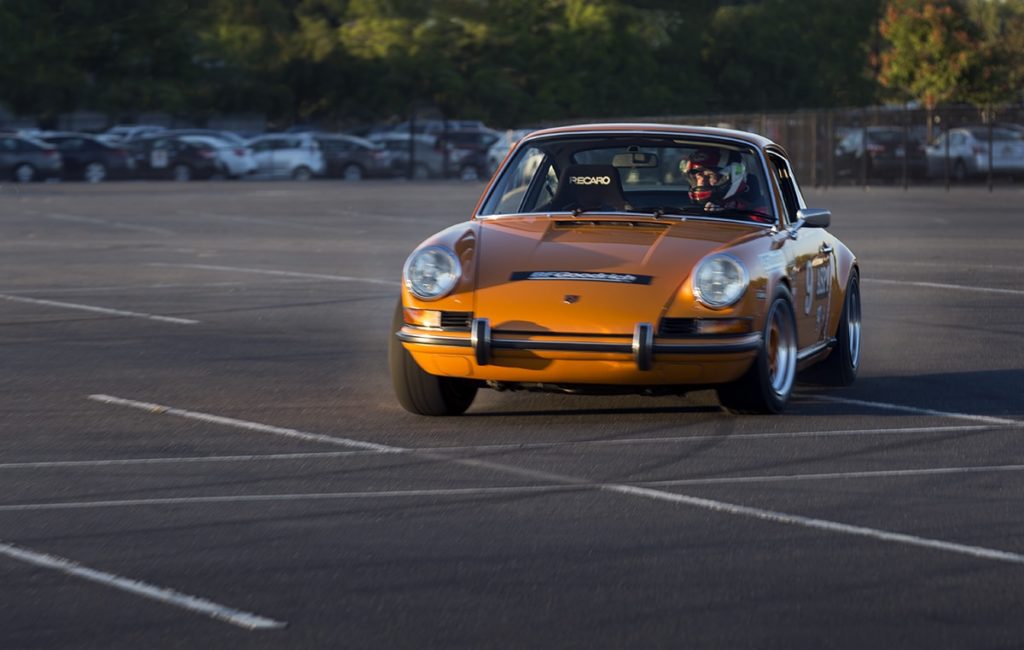

As described in Part 1 of this story last month, Dwight Mitchell’s persistent competitive streak and his old 1971 911 are the stuff of legends. The car’s current owner and fellow racer, Pat Costin agrees, “It’s rumored it has more race wins than any other car on the autocross circuit. I know it’s the first Porsche 911 to exceed 1.0 G shod with street tires. And after Mitchell’s retirement from autocrossing in 1998, the PCA Sacramento region saw fit to retire racing #30, so I run #9.”

It all started in 1981 when Mitchell saw the potential of the rear-engined Porsche as an autocross platform. That’s when he decided to put SC flares and valences on the ’71 coupe he had bought from Skip McQueen. To optimize the suspension he special ordered 8 & 9 x 15 inch Revolution wheels with a unique offset. Originally he used Yokohama tires, but later moved to B.F. Goodrich Comp T/A R1 race rubber, which he helped to develop.

The Signal Orange 911 would go on to became the test bed where Koni perfected its double adjustable shocks, Weltmeister created its adjustable sway bars, and Automotion developed its adjustable spring plates.

“The Automation spring plate we helped design made it easy to change torsion bars without having to alter the alignment,” Mitchell recalls. We typically ran 22mm torsion bars in the front, although occasionally we would switch to 21s for a bumpy course.”

“We started increasing the rear torsion bars with 27 in the rear for non-flared early 911s, then moved to 28s with flares, and 29 as the rubber got better,” he recalls. “We also put a ton of freeload on the 901 limited slip transmission. AFKQV were the gear ratios chosen, and in 50% of the autocrosses I used 3rd gear as well as 2nd.”

One of the challenges Mitchell had to overcome was running out of shock travel when the car was lower. So he talked to Koni, and developed a shorter competition shock with a spacer. “We would tune the suspension from run to run,” he remarks. “Sometimes I would change front toe, if I was experiencing understeer. I played with tire pressures a lot, and that’s why I eventually helped design the adjustable Weltmeister sway bars.”

Mitchell explains, “My theory on sway bars is to run the softest sway bar that you can. To me the sway bar is merely a tuning device. To get a car to turn in you have to have soft springs. To keep the inside front tire on the ground, you have to raise the rear roll center to the point where you can run enough spring rate in the back that it won’t squat as much. In autocrossing, exit speed on the corners is key. I tend to toss the car, so I needed a little more understeer on the front of the car than the average guy.”

He continues, “911s are a particularly difficult car to stop because you have to run so much negative camber in the front (typically 1.55 to 1.59) to get the car to turn. There’s would always be some toe out too. Negative camber in the rear is equally critical. We would tend to run -2.35 degrees. We spent one whole year in 1987 just experimenting with rear toe out, coming up with a value of 3.64.”

Mitchell also developed special camber plates and bushings. “By the rules you could not use spherical bearings in the suspension. You could change rubber to plastic, but you couldn’t use metal. So, I found this stuff called ‘Turcite’. It was used to lubricate the space shuttle. You buy it in a big long tube and machine it to fit. It’s self-lubricating, harder than Delrin, and non hydroscopic. The reason Automotion went to Delrin was that Turcite was very expensive, and every bushing had to be machined from scratch.”

“There are so many things developed on this car that everyone uses today,” Mitchell sums up. “I never wanted to take myself too seriously, even though I probably won 90% of events I entered in autocrossing. I guess I had a good run.”

Now that’s an understatement.

Article Copyright Randy 2017 Randy Wells. All Rights Reserved.