Wash, clean, wax

Battery (replace)

Oil Pressure Gauge (repair)

Custom car cover (buy)

Original wheels, tires, original brakes (find)

Original small outside mirror (find)

Original steering wheel (find)

This was George Reilly’s to-do list when his 550RS/1500 Spyder arrived at his home in Florence, AL. He’d acquired the car – 550-0090 – from its current owner Dick Barbour – by a phone call and a series of certified letters in late October 1971. He and his wife Liz were Porsche owners – he had a 1969 911E. An uncle a decade or so earlier had owned a 356 and given him rides, sinking the hook deep. “When I was in college, I found one sitting in the back of a gas station at the University of Michigan – a 1954 1500 Super – which I bought for $1,500 between my junior and senior years,” he recalls. A stint in the Air Force sent the Super to a new home. A job after that allowed him the opportunity to buy the 911E.

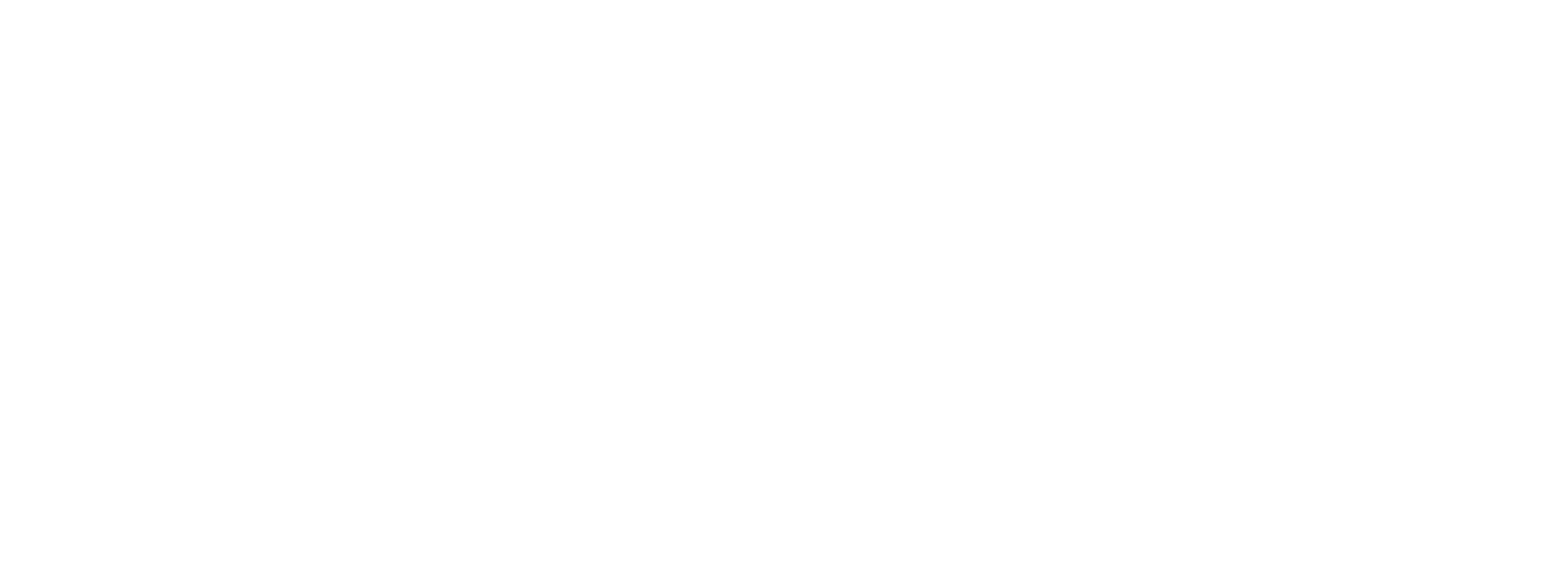

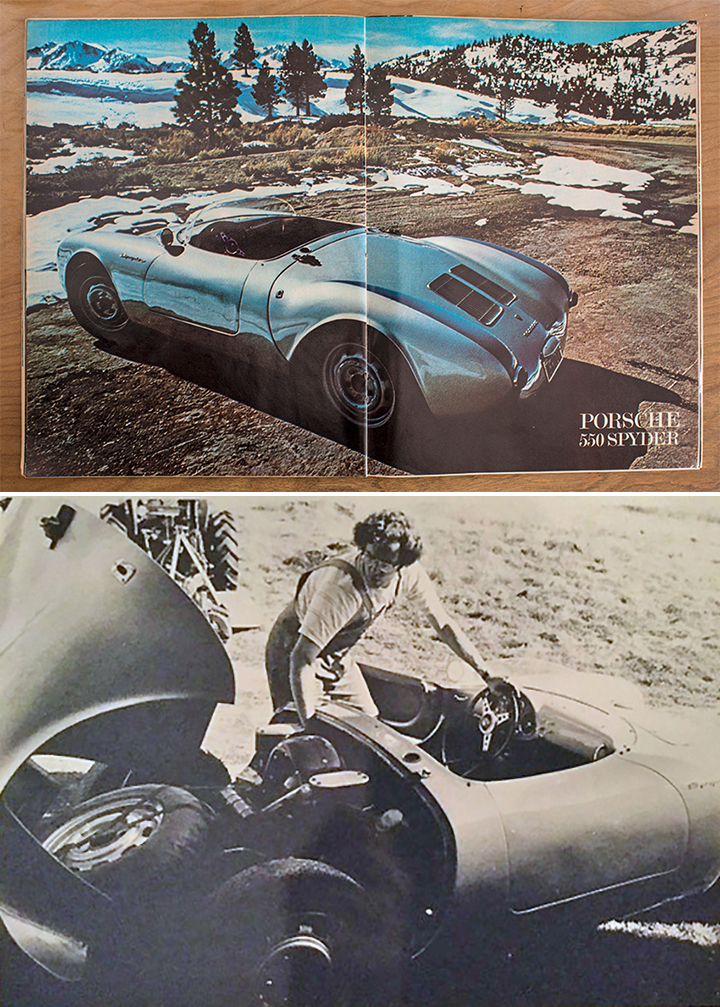

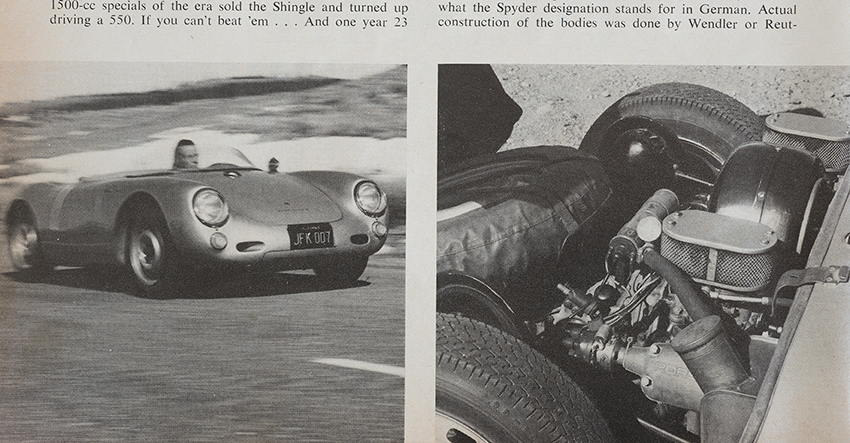

In June 1971, Road & Track magazine published a multipage story, “Salon: The Immortal Porsche 550 Spyder.” Leading off with a sensual two-page photo by R&T art director Bill Motta of a Spyder in the spring thaw of California’s Sierra Nevada Mountains, the four-page story that followed – written by executive editor Allan Girdler and seasoned with more evocative Motta images – rhapsodized about how, as the story called it, “Porsche Racing History Began with the Giant Killer.”

Call this Porsche Porn from the early 1970s.

Girdler invited Richie Ginther, already an American racing legend, to come drive the car and offer observations and impressions of this Porsche racer. Interestingly, however, this car was a racer that never had raced.

The car in R&T’s story – the same 550-0090 that arrived in Reilly’s driveway months later – belonged to Fred Sebald. “The present owner, Fred Sebald,” as Girdler wrote, laying out the provenance of the 550, “had been longing for a Spyder. When the Spyders were the competition machines, Sebald was the race car body repairman. When Ginther and [Phil] Hill and [Johnny] Von Neumann and their peers shunted hay bales and each other, Sebald made things right again. So he knew and appreciated 550s.”

“My interest in the Spyder,” Reilly explains, “was part of my learning curve. I wasn’t looking for a Spyder in my world, which was pretty much series production cars at that point. Then I saw this story, which was particularly salivating.” Reilly found 0090 advertised for sale in an issue of Competition Press & AutoWeek magazine shortly after the R&T piece appeared. He dialed the number in the ad and it rang into Dick Barbour’s racing shops in La Mesa, CA. Barbour and Reilly carried on a certified letter correspondence that included a pair of checks to Barbour and a planned delivery date to Reilly. In those days, Barbour not only was racing but he also was brokering racecars and he had a transporter heading east toward Florida. There, one of Barbour’s mechanics loaded the Spyder onto an open trailer and delivered it to George and Liz in Alabama.

Reilly’s experience with Porsche racecars at that time was similar to most enthusiasts’ history even today: read the stories, see the pictures (or now the videos), and experience lust.

“Once I had my hands on the car and got a chance to drive it, to see how a competition car drove compared to a series car, I was hooked. And I drove it! The roads in Alabama were pretty sweet for driving. While we lived in town, country roads were just a couple miles away.

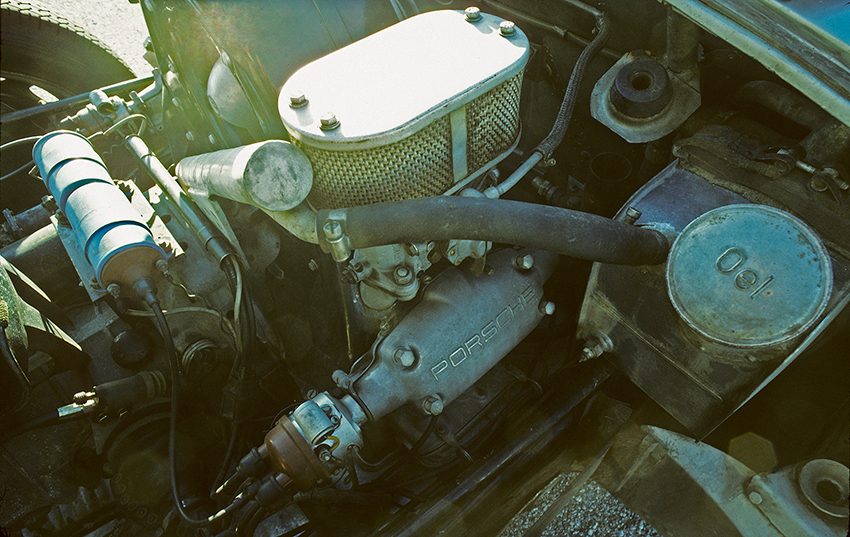

“The car had maybe 110 horsepower,” he continues. “It was a car you had to go through the gears running it up pretty much to redline to get the maximum performance out of it. I remember the throws on the gearshift were quite long. It had a lot of nice features – a lock out for reverse. And Speedster-type seats with virtually no padding! But the car had full road equipment – turn signals, horn, daytime, and nighttime lights. A top!

“The car ran with vegetable oil, Castrol R, which made it so wonderful to drive. Because every time you let the engine wind down, the odor of that bean oil came wafting over the back of the car and into my nostrils.”

The history of 550-0090, by the time it landed in Alabama and later moved with the Reilly’s to their current home in Massachusetts, listed a who’s who of interesting non-racing personalities. The first registered owner was Willet Brown, whom Wikipedia describes as “an American television pioneer who co-founded the Mutual Broadcasting System.”

Brown thought he wanted a sports car to commute from home to his office. Girdler analyzed Brown’s ambition: “In 1956 as now, there was a glamour attached to racing cars, and there were people who thought they’d like to drive to work in the hottest racing car of the day. Of those who could buy the latest in winning cars, some did enjoy the experience, and some didn’t.”

Turns out Brown didn’t. He took delivery with 16 test miles on the odometer that Porsche’s chief racing mechanic Hubert Mimler accumulated around Stuttgart before releasing the car. Brown sold it – at 634 miles – to George Duvall of Woodland Hills, an L.A. suburb in the San Fernando Valley. Duvall was an early car customizer on the southern California car scene. He drove the car, taking the odometer to 12,500 miles when he sold it. The 550 next went to Leonard Harris, a former writer and Hollywood actor who had a minor role in the 1976 film “Taxi Driver.” He added another 1,900 miles before selling it to emerging southern-California Porsche eminence, Vasek Polak. Robert Fleischer acquired the car from Polak with just 34 more miles, bringing the total to 14,434, according to a bill of sale dated September 7, 1963. Fleischer also enjoyed the car, bringing the mileage to 18,317 by August 25, 1964, when he sold 550-0090 to one of Polak’s salesmen, a man known only as “Hank” following “a big service at 18,051 miles.” In 1967, Fred Sebald acquired the car from “Hank”, and he developed his own to-do list:

- Speedo shows correct mileage minus 30 miles

- Engine is stock

- Clutch changed to large later-model diaphragm clutch

- Castrol R 40 weight oil only used

- All shocks replaced in 1967

- Fuel system cleaned and all fuel replaced with Castrol racing fuel

- Removed drum brakes and installed 1965 disc brakes

- (Here Sebald listed the previous owners as identified above)

- Installed roll bar

The Road & Track story explained that Sebald, grown weary of repairing race cars in L.A., relocated to June Lake, CA, an idyllic spot known for winter skiing and nearly year-round fishing in the Sierra Nevada Mountains about 325 miles north of L.A. It was there that Girdler and Motta found Sebald and connected the car with racer Ritchie Ginther. Shortly after the R&T story, Sebald sold the car to Barbour who, soon after that, sold it to Reilly. End of story.

Not quite.

“If you look carefully,” Girdler wrote in the June 1971 R&T story, “you’ll see there are ripples in the doors, caused by careless types who leaned against the aluminum. Those are the only flaws on the car. One of the justifications Sebald used when he bought it was that the Spyder would be a wonderful ad for his shop. He meant to restore it.

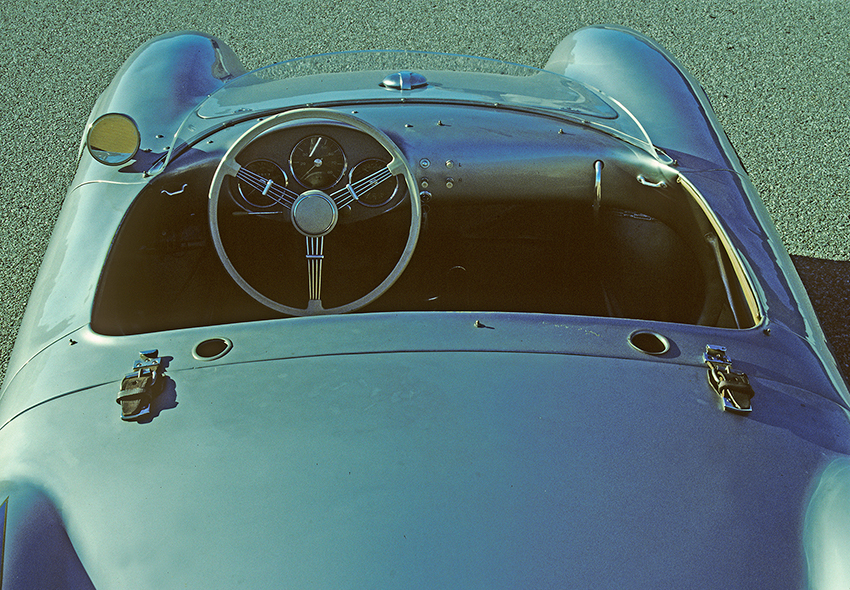

“But he couldn’t bring himself to do it. Whatever else they were, the previous owners were careful. Not only has the car not been raced, that’s the original paint.” And that was June 1971.

“That was the condition of the car when I got it,” Reilly echoes Girdler. “Original. Unraced. Unrestored car, and it was the last 550 Spyder built! Other numbers came later but they were – according to the Spyder book – chassis replacements for wrecked racers.”

Some years later, Reilly loaned 550-0090 to a friend who was restoring his own 550 and wanted the original to confirm authenticity. That project took two years, and after completion, the friend’s car won the Porsche Club’s ultimate honor, the Manhattan Award. Sometime after that, the friend sold the car to one of the collecting world’s most discriminating and demanding members.

“I’ve always been particularly sympathetic to the cars I’ve owned,” Reilly says. “I drive them within their limits, and I treat them with respect. And because this was a truly original car, I really felt I had a responsibility to protect it.”

R&T had published a road test in its February 1957 issue, using a car another southern Californian, John Porter, offered them. In the story, most likely the work of editor John Bond, he wrote, “Driving the 500 is very little different from handling a production Porsche Speedster or coupe… Of course, the performance literally forces you back in the seat, but surprisingly the thrill wears off rather quickly, especially on a lonely road with little or no traffic.”

Southern California Porsche enthusiasts may feel free to sigh now.

“What was it like to drive,” Girdler asked in his 1971 story on 550-0090. “Very like a standard Porsche, in the opinion of both these testers of 15 years ago and Richie Ginther now. The steering, Ginther said, ‘was completely familiar.’ The gearshift and brakes were good then, not so impressive now, although it’s not really fair to make such a comparison.” Ginther, who died in 1989, had plenty of experience in 550s, driving one Johnny Von Neumann throughout 1955.

Reilly concurs. “Very neutral steering,” he recalls. “I found the car to be kind of easy to handle. It didn’t feel excessively light or have the tendency to drift. This car tracked straight and true. It was delightful to drive, not unlike a Speedster, but without the potential for oversteer. You didn’t get that swing-axle lift.” He recognizes that cars provide completely different experiences from road use to racing conditions. He also is first to admit he is no Richie Ginther. “This was a 120-mile per hour car. I know I saw 90 in my car. But I’m pretty sure I never saw 100 in it.”

Reilly has owned – at the same time – a 550, an RSK, a 904, and a Carrera Speedster. “I never ever had a repair bill for those engines,” he says. “I either was the luckiest guy in the world or… I’d like to think it was sympathetic ownership. When the oil was warm, I drove it hard. Someone told me early on, the best way to drive a Porsche racing engine was to drive it like you hate it.”

Reilly hated it just enough. And then it broke his heart. In the early 1990s, business reasons forced him to part with 550-0090. It went to another good home. He had owned and enjoyed the car for more than two decades, the longest single ownership that included regular exercise.

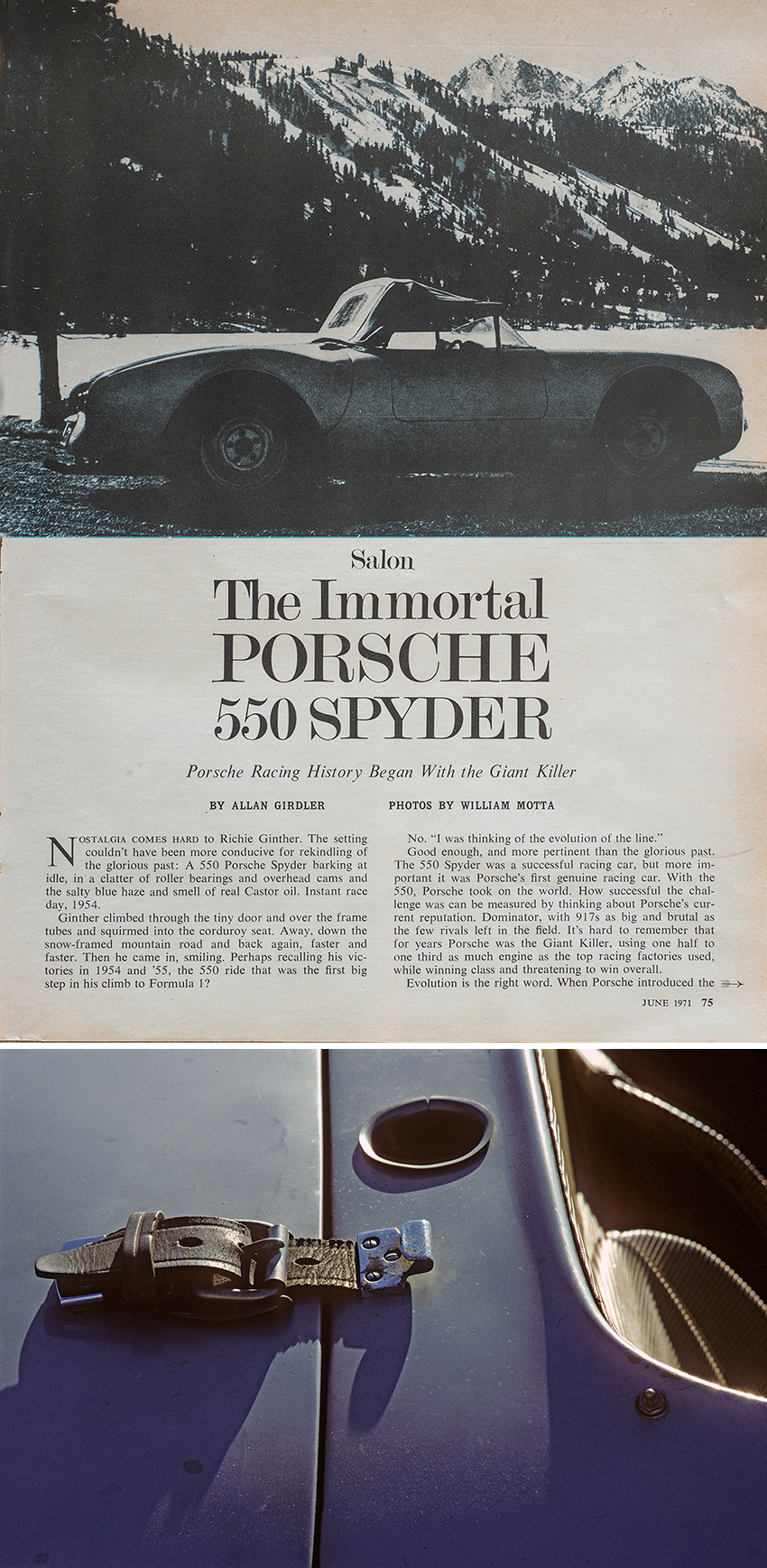

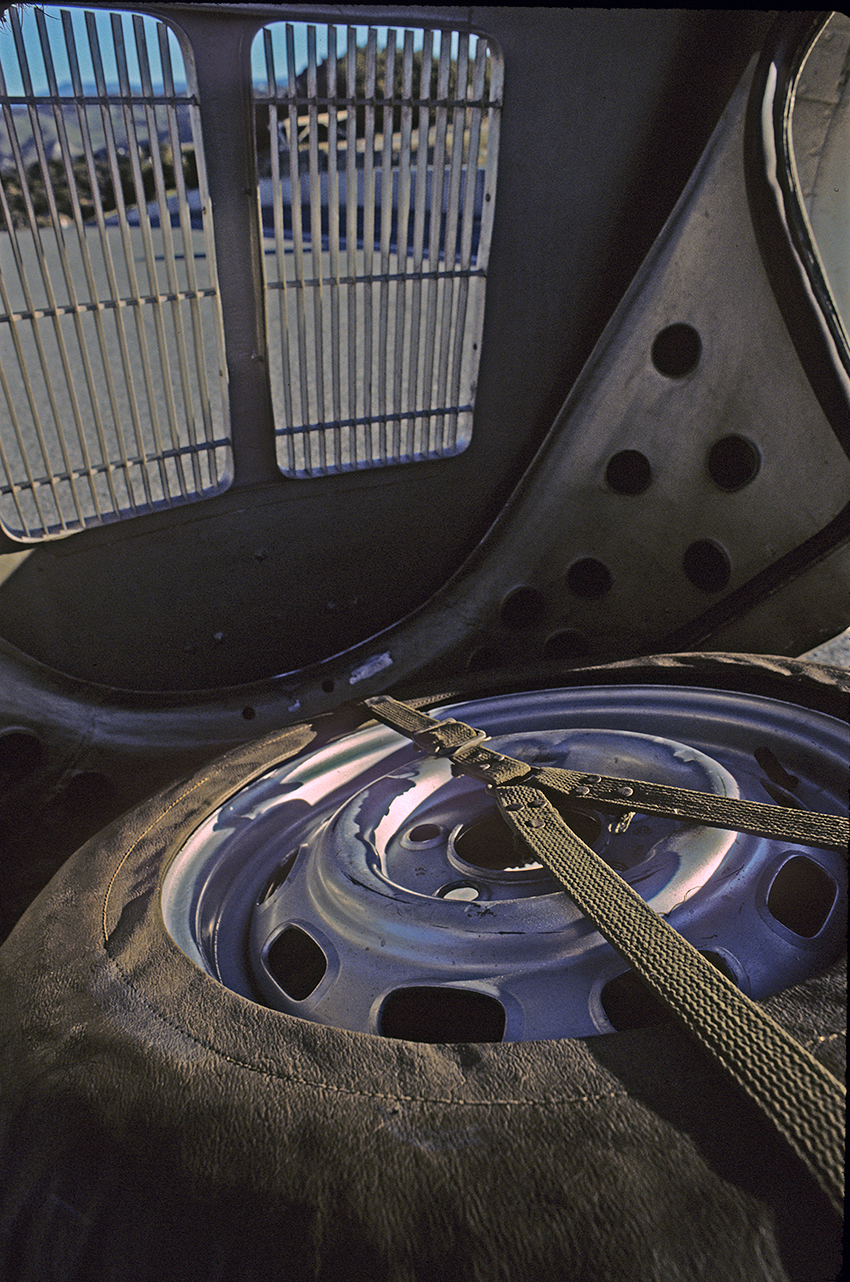

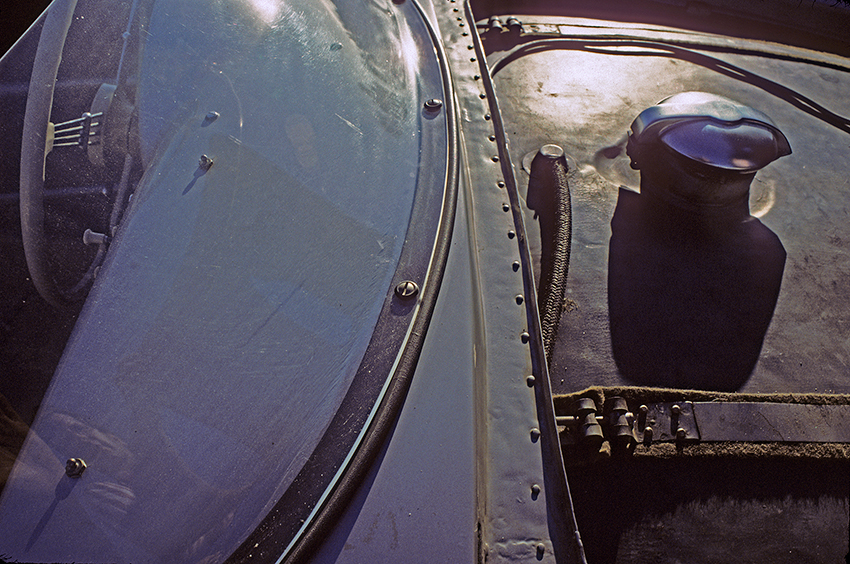

“The car as it stands today is 99 and 44/100th’s percent Pure,” he says, recalling the old soap advertisement from the 1950s. He sourced an original brake system and replaced the discs. He removed Sebald’s roll bar. He replaced Sebald’s Les Leston sport steering wheel with an original Banjo-type 550 wheel. “Stuff that’s unique to ‘0090’? Well, first of all, the car has a top. Most people threw it away because they had no need. I never folded that top…

“It’s got the full belly pan! Race mechanics immediately took that off to have access. The other consideration is that it’s a fire hazard because leaked oil collects there. It has special raised sections clear the exhaust. It has louvers for cooling. And it has leather boots to go around the exhaust.” The inventory continued.

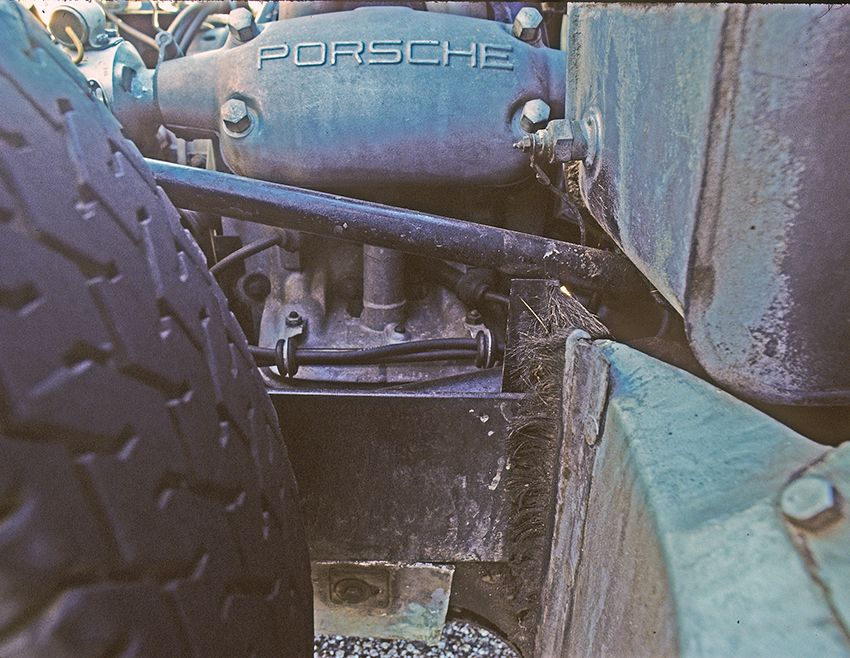

“The car has rear trailing arms on it that go through the firewall. There are brushes that act like gaskets to keep dirt and debris out of the engine compartment.”

“It has the original ‘quick jack’. It has a collapsible handle. There’s a hole in the frame next to the passenger seat and the jack slots right in there. There’s a leather strap that holds it in place. Most racers threw those away to save weight.”

He paused. “I haven’t thought about this car for a long, long time. The Germans are so fastidious about this stuff. Beginning with the Carrera Panamericana road race – and their successes at Le Mans – they were on a roll,” Reilly explains. “These cars evolved. By the time they got to the RSK, the passenger seat was a hammock. And having [as he did] the RSK and the 550 right next to each other was quite a contrast. No door trim on the RSK, no brushes on the suspension, no belly pan.

“The 550 really was very well appointed for a competition car,” he remembers. “This is even more obvious when you think about what they took out of it over the next two years.”

This well-appointed 550-0090 went to Bonhams’ Goodwood Revival sale as lot #140 on September 10, 2016. In their catalog they wrote, “In offering this mouth-wateringly original, unmolested and intricate ‘time machine’ 550RS Spyder, we feel privileged to present what is considered to be the world’s best-preserved, never restored example of this seminal Porsche surviving today…”

Bidders agreed. When the sale was done, the world recorded a new benchmark for a 550RS/1500 because 550-0090 sold for $5,940,061 including fees according to Bonhams website.