Photos by Randy Wells

You’ve probably read enough analogies of sports cars, fine cameras, and luxury audio equipment in high-end lifestyle magazines to get the idea that journalists are passionate about these things in a big way. I’m not immune, and vinyl records, Leica rangefinders, and Porsche 911s have been a fascination of mine since 1964.

That’s when I bought my first LP, was gifted a Kodak camera, and was introduced to the early 911. I immediately fell in love with the feel and sound of the long playing record, the shutter advance of the film camera, and the Porsche 911’s hooligan nature with its air-cooled flat six barking a nasty exhaust note. School and financial obligations kept me from fulfilling my dreams of ownership for a long time, but I promised myself that someday, some way, I would own a top-notch analog stereo system, a Leica rangefinder, and a pre-‘74 911.

Before we come to all that, let’s turn our attention to the early 911.

Just to review what you undoubtedly already know: these fabled Porsches were hand built by craftsmen in Stuttgart Germany between 1964 and 1973. They are exquisitely formed, simple to work on, extremely functional, and lack the smog and safety regulation equipment of later sports cars. They also have a power-to-weight ratio that was unsurpassed until the 1976 Turbo. At less than 2,200 pounds and up to 210 horsepower available, they are both quick and nimble.

Accelerating out of an uphill bend with all that mechanical intake noise behind you is a hoot, and the simple exhaust system’s raspy wail is an added bonus. The pure aesthetics, chrome trim, and dainty bumpers of Porsche’s original 901 design are traditional features that make them the preference of many enthusiasts. They are arguably among the best of the late ‘60s and early ‘70s automotive icons – true sports cars, not the civilized grand touring types that many marques later became.

It wasn’t until 1997 that I purchased my first “early” 911 – a 1972 911S coupe in Metallic Blue with mechanical fuel injection. It had 48,000 original miles and had been well maintained by three previous owners. In the words of one Porsche enthusiast, “you want a light, visceral, scary, nasty, feels-like-an-accomplishment-to-drive sports car without anything to interfere with your sensory experience.” And that’s what I got. No power steering, no ABS, no stability management, no traction control, no driver’s aids, and minimal sound deadening.

I drove that ‘72S to dozens of track events, competed in numerous autocrosses, and toured from Seattle to California via back roads four times over the next eight years. Along the way I also learned how to repair it and find the parts when they needed replacing.

My history with cameras is remarkably similar. I learned to photograph with a Wetzlar, Germany-made Leica M3. I developed my first roll of black and white film in 1977. That rangefinder camera led to many more 35-millimeter Leica cameras and lenses, which have a smoothness and mechanical precision missing from many other models. I still love using analog Leicas for their purity, quiet shutter, and silky film advance lever. However, as the industry changed and photography became my profession, I’ve adapted and made the transition to digital cameras.

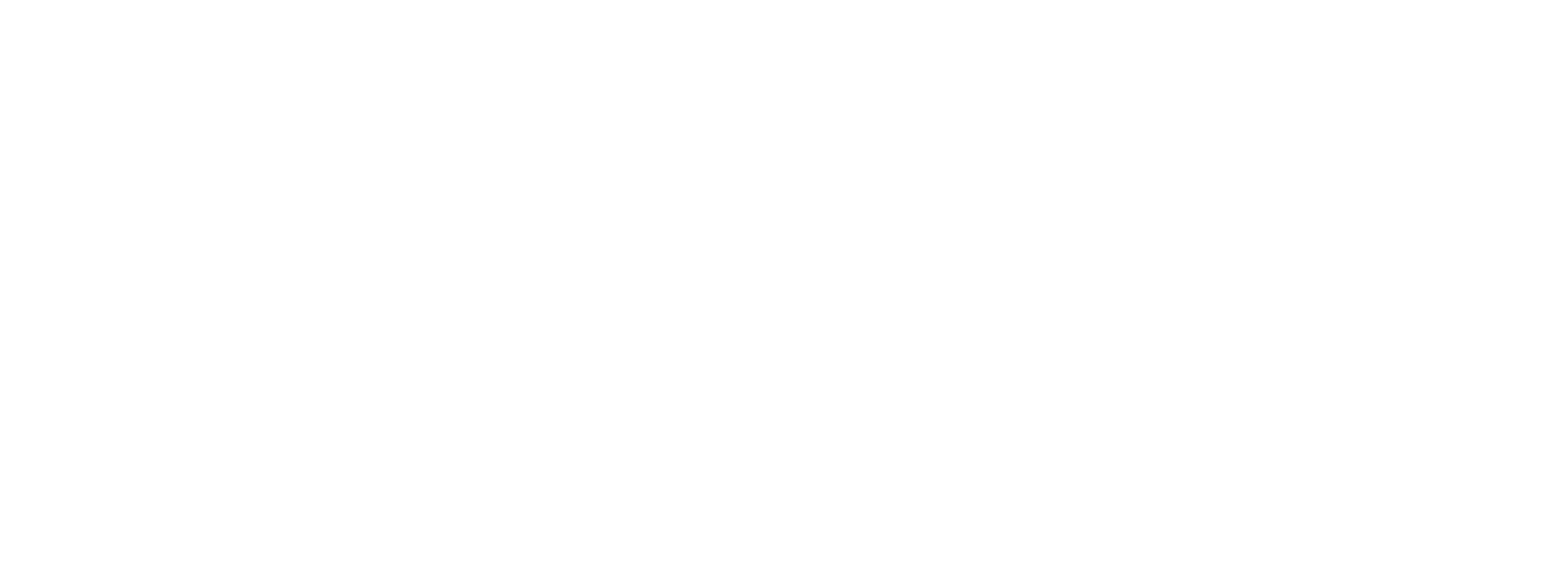

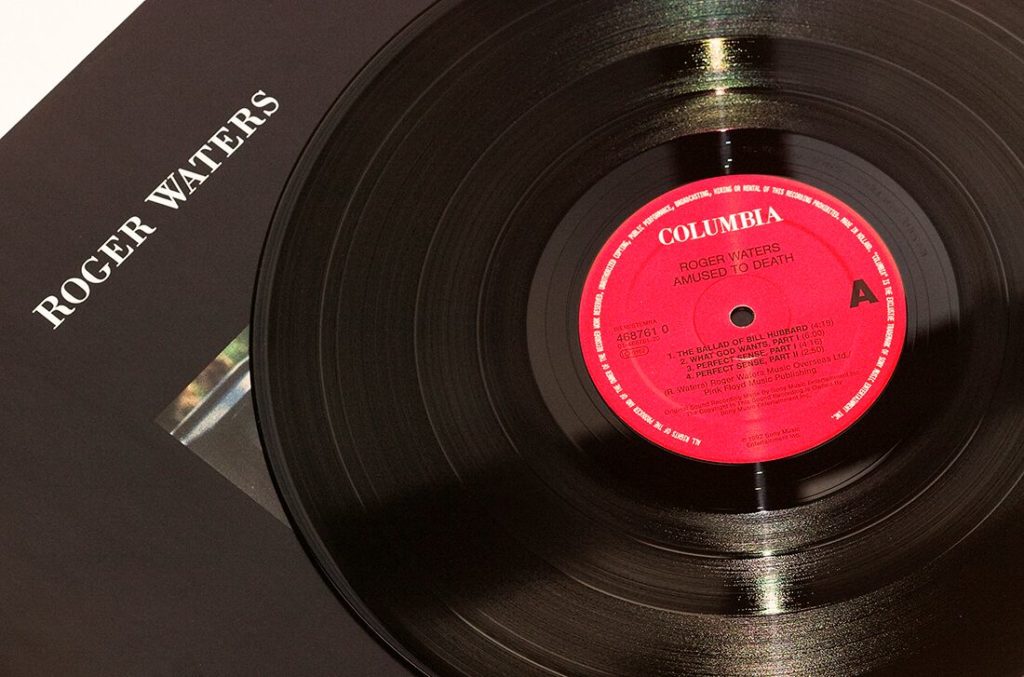

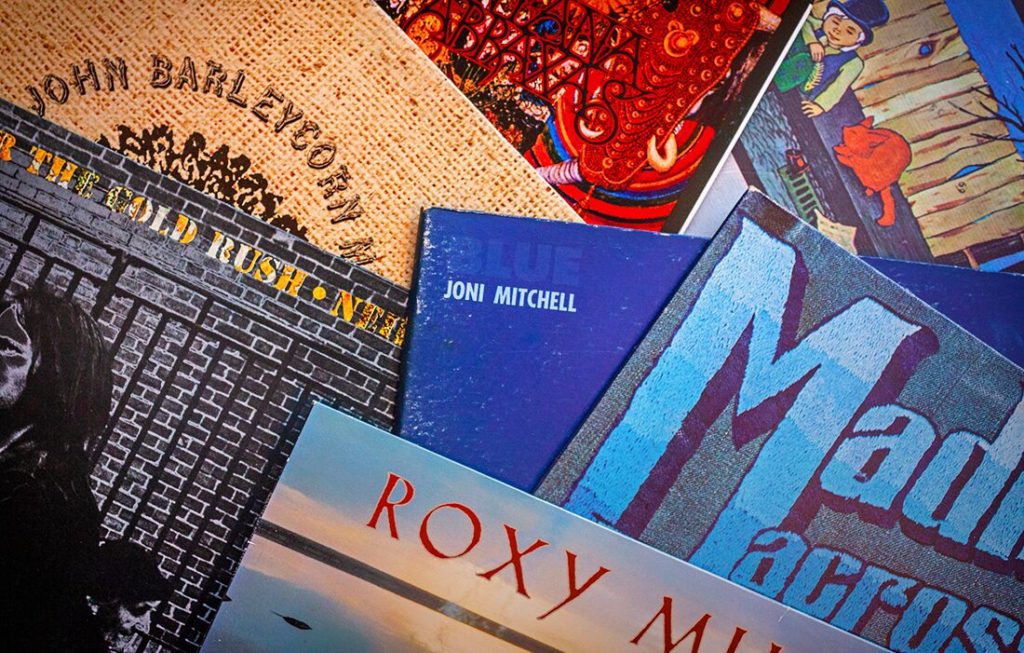

My audio hobby, another temporal experience, has taken a similar course. In the mid ‘80’s, I won a photo contest and used the money to buy a high-end analog stereo system. Finding original LPs soon became my passion along with photography. The Beatles, The Who, The Rolling Stones, Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, you name it – I was buying whatever LPs the new CD converts were dumping. My turntable and audio system continued to improve over time, and eventually I ended up with a top-of-the-line analog rig matched to tube electronics and big planar speakers. For everyday listening, CDs certainly fit the bill. But for those times when I really want to savor my audio system, vinyl rules the roost.

Having lived with early 911s, Leica rangefinders, and a vinyl based audio system for a few decades, I can tell you that each of these hobbies require more time, commitment, and care than their modern day equivalents. For example, a later water-cooled Porsche 997 demands much less maintenance. And when parts do wear out, new factory replacements are easily available. Similarly, CD players are essentially plug and play appliances requiring little attention until they fail. When it comes to digital cameras, they are inevitably replaced every few years due to the rapid advances in technology.

Yet for many enthusiasts, continuing to use vintage technology has proven more satisfying than living within the confines of a world determined by convenience.

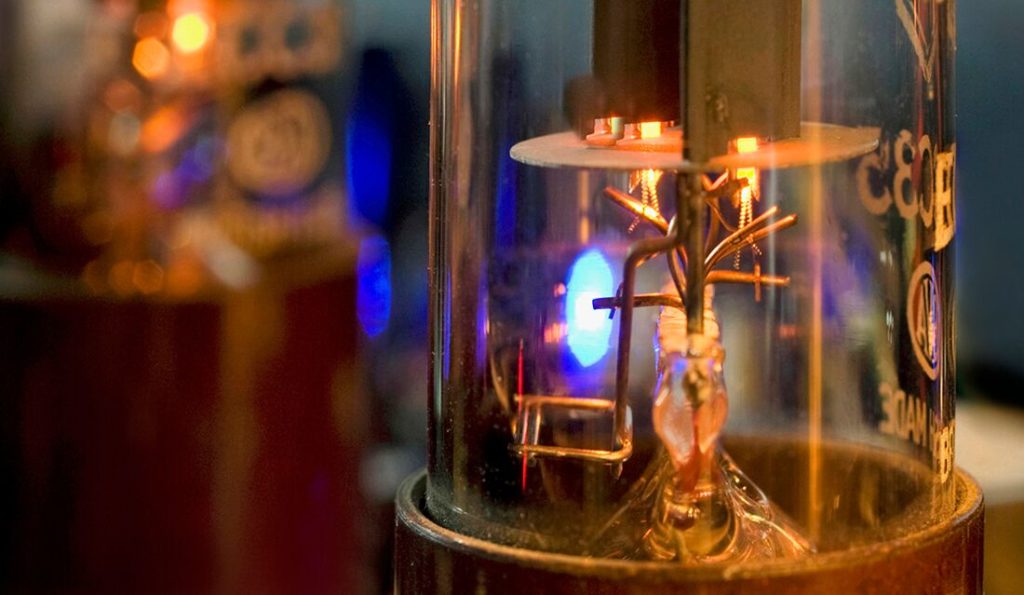

There is a built-in ritual to enjoying these artifacts from the late ‘60s and early ‘70s that is ultimately engaging. Unlocking a car door by hand, carefully loading a roll of film, and landing a diamond stylus on the outermost groove of an LP are just the beginning. Pull up the hand throttle, manually focus the lens, clean the stylus. Then listen as you warm up the engine, hear the brass gears work as you advance the film and cock the shutter with your thumb, and revel in the sound generated from an LP. These old school pastimes are quick to let you know when you are doing something wrong and are equally ready to reward you when you’re doing it right.

At times it seems like these “dinosaurs” from the past defy the laws of physics. How does a rear-engine air-cooled sports car stay on the road without over-steering into the bushes in a hot molten mess? How does a shard of diamond trace the grooves of a fragile vinyl record without ruining it? And how does a camera that fits in your jacket take pictures that rival or surpass those made with the best full-size digital 35mm SLRs? Or even larger format cameras?

Still, there’s no denying that “hassle-free” is not an adjective applied to these pursuits. Old Leica cameras need to be exercised and periodically lubricated. Vinyl records have to be cleaned and handled carefully. The turntable you play them on needs to be aligned and leveled, and the phono cartridge needs to be periodically replaced and aligned properly. A fresh suspension is needed to allow for the fullest performance and experience in an early 911. Parts wear out, they can be hard to find, and NOS stuff can get expensive. Not to mention non-galvanized metal rusts badly when the going gets wet. It sometimes seems like it never ends…

So why do “obsessive nerds” cling to artifacts from the past and continue in their quest for experiential freedom? Why do they prefer a mechanical Rolex Submariner to an Apple watch? Well, for one there’s a considerable amount of “feel” involved in these arguably archaic hobbies. They are more art than science.

Perhaps it’s not technology that will get you all the way there. Perhaps intuition and a willingness to be open to something else are necessary to achieve that elusive bliss we strive for. The payoff is a feeling of satisfaction when the visceral pleasure of playing a great LP, using a mechanical rangefinder, or driving a fine vintage sports car well is truly experienced. Even ordinary tasks become part of the appeal of caretaking something so old, unique, and inherently valuable. The retro-cool resurgence in vinyl, vintage cars, and film could be proof of this.

Turning back to cars, some would say that it’s in the actual use of a vintage Porsche where the largest differences become apparent. The mechanical fuel injection of a ’72 911S allows for throttle response that a drive-by-wire ‘90s Porsche can only dream of. Want to rotate the car mid-corner? Simply lift off the accelerator pedal and the back end comes around. Then it’s back on the throttle for a power slide that’s not inhibited by a computer chip that thinks it’s smarter than you are.

With the latest offerings, there are so many automated driver’s aids, that you are left with little to do except ponder grand touring and modern day conveniences like the latest GPS system and a cup holder. In reality, these current day “sports cars” are so capable it’s hard to notice that they weigh more than 3,000 pounds. In contrast, an early 911 is less than 2,300 lbs. This allows for its driver to revel in handling limits, while still remaining under the speed limit. A new GT3 needs to be taken to the track to experience what is possible, but if the driver’s skills are not up to the task and they run out of grip… well, the car will probably be traveling too fast for anyone but a race car driver to keep from hitting something.

In the vinyl world, much of the above rings true. A high-end turntable allows for many performance advantages and upgrades over even the best digital players. It’s becoming more and more the norm that LP playback is the high-res medium of choice for audiophiles. For them, there is a warmth, richness, and presence to analog playback that eludes most CD or SACD masterings. Feel like tweaking a digital player? Not that easy I’m afraid. How about viewing the album’s artwork? Bring your magnifying glasses out if you want to read the disc’s booklet.

Analog photography is coming back online too. The reintroduction of Ektachrome film and Polaroid cameras is just one indication of this. Go into any major brick and mortar camera store (at least those that are still around), and you will see young people mulling over what old technology to purchase. Some are even going back into the darkroom to extract all that’s hidden in a black and white negative.

In my experience, the visceral experience of analog is simply lacking in the digital realm. For vinyl, there is a focus required to properly set up a turntable and research the best sounding vinyl. This is in contrast to simply flipping through music selections on a smartphone. Listening to music on a turntable requires paying attention to the process of playback and the concept of an album as the artist intended.

Extraordinary in their flexibility, simple in design and execution, yet incredibly rich in potential – vintage cars, film cameras and vinyl are actually closer to one another than you might imagine. These old-school pursuits have a tangible “in-the-moment” charm that’s undeniable. It’s not surprising then that many developers of the best turntables available today favor older sports cars. They believe that earlier designs are simply more organic and reward the senses in a way that newer technologies cannot quite approach.

Debating whether this viewpoint is right or wrong in today’s world is missing the point. Besides, what is the point when folks would rather text each other than discuss something in real time? Yes, exploring these leisure time pleasures can be challenging. Yet, it’s hard to argue that the experiences lived along the way exploring the subtle variations of these hobbies can bring a joy and fulfillment that’s unmatched by more convenient paths.

For some it still remains the journey that counts. If you are so inclined, now’s the time to find that original LP, cue up your favorite track, take a drive in a vintage sports car, and pull out an old Leica M3 just to load another roll of Tri-X. Getting there can be half the fun – heck for some, it’s the only thing that matters! Enjoy your “archaic” pursuits for all they offer you, and savor the mechanical thrill of these magical hobbies knowing that they continue to grow for some very good reasons.

Article and Photos Copyright Randy Wells. All Rights Reserved.