Photos by Randy Leffingwell and Courtesy of Porsche Archive

“Victory has a hundred fathers and defeat is an orphan” came from the pen of Count Galeazzo Ciano, Benito Mussolini’s son-in-law, and written in his diaries during World War II. The better-known aphorism “Success has many fathers, failure is an orphan,” merely paraphrases the original and has made it easier for many to claim it as their own. Such is the nature of ambition and accomplishment.

That one Porsche success had many fathers, however, is beyond dispute. The Typ 356 Speedster, honored in the accompanying story “Speedster Wars” grew from two fertile minds in the U.S., two entrepreneur/racers who understood America’s interests in and ambitions for capable, lightweight automobiles. Maximillian Hoffman, born in Vienna, made his name and his fortune importing and selling European cars in New York City. When he met Ferry Porsche, the car maker was interested in selling cars in the States, but when he modestly admitted he hoped Porsche might sell six or seven cars a year in America, Hoffman scoffed, “If I can sell six or seven each month, I’m not interested,” he reportedly told Ferry. Hoffman had owned and raced a Glöckler Spyder and his customers’ interest in that car led him to propose to Ferry a run of flyweight open cars for racing. Because Hoffman had proven he could sell six or seven or more cars a month – including several through his ambitious southern California distributor John Von Neumann, Ferry complied.

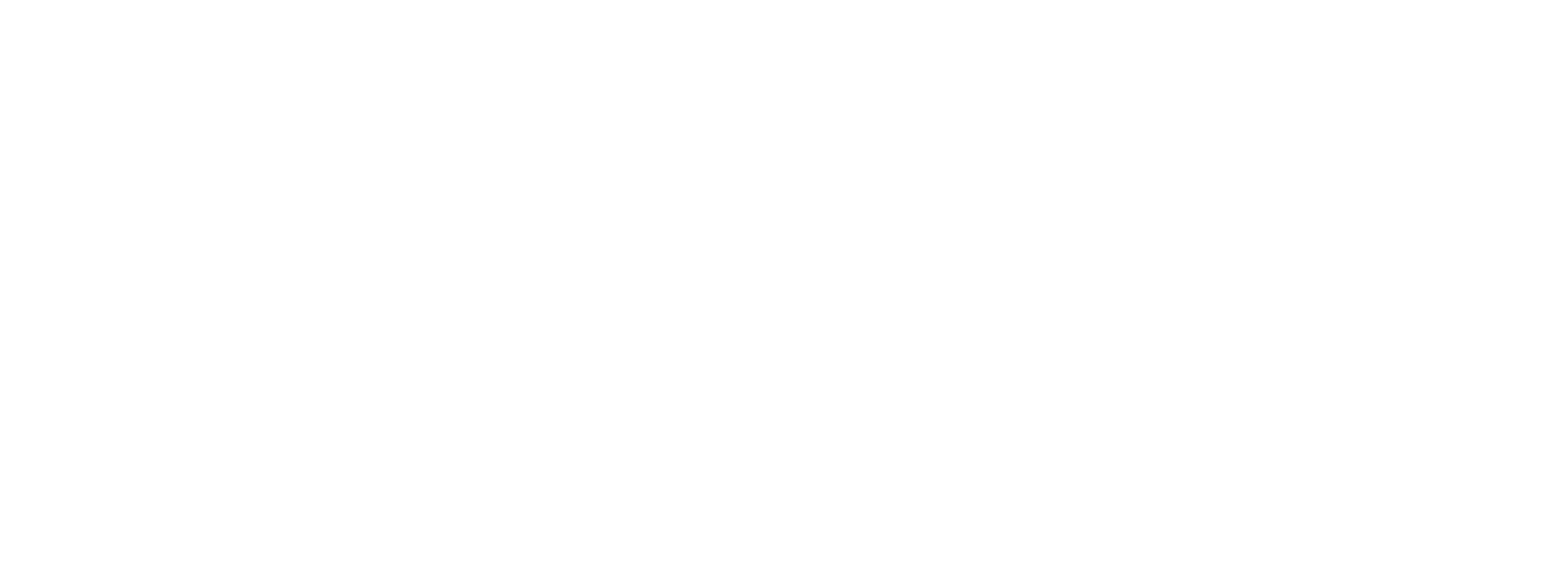

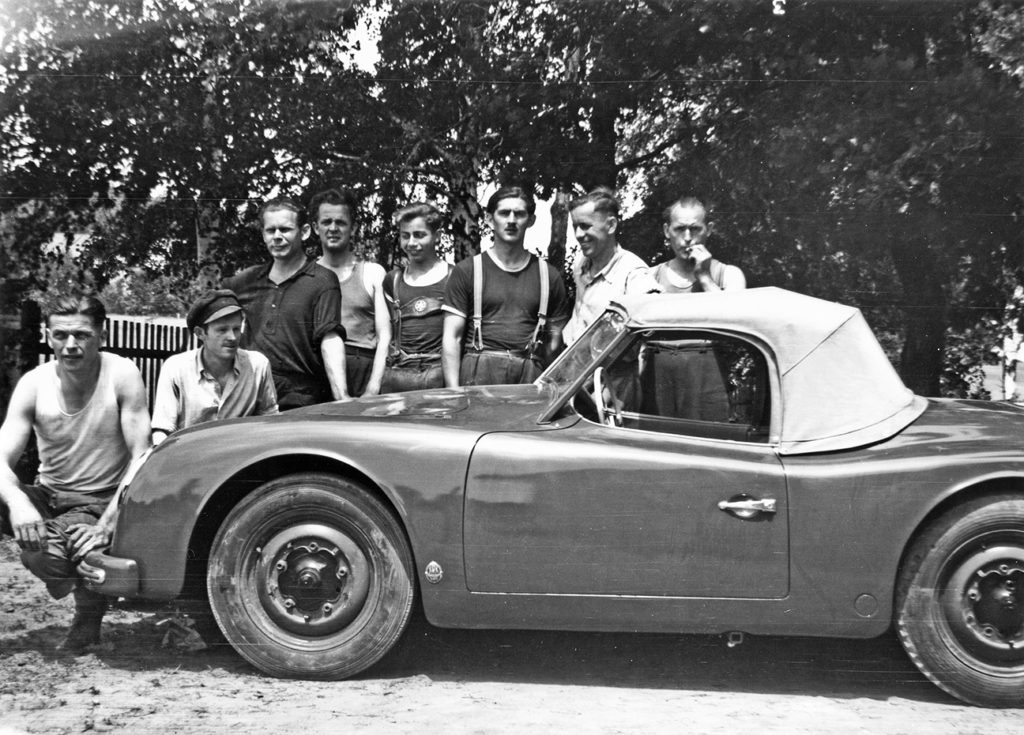

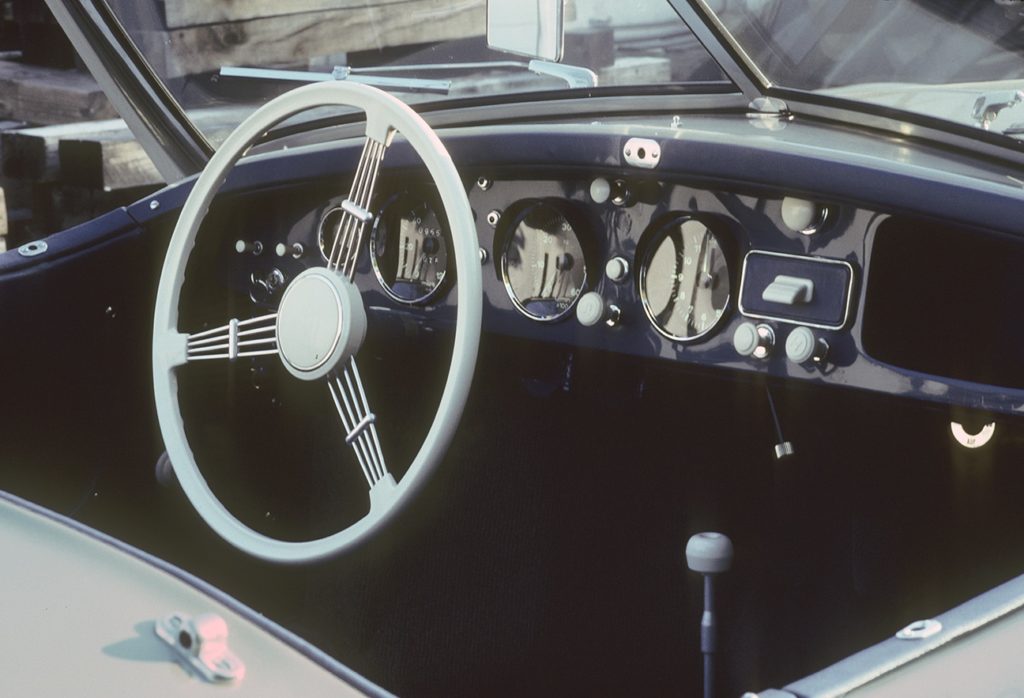

His chief body engineer Erwin Komenda and his new chief modeler, Hans Klie designed and shaped a new body in aluminum for the 356 Cabriolet floor pan, engineers fitted it with the 70-horsepower Typ 528 1500 Normal engine and Porsche’s chief engineer Karl Rabe gave it the Typ 540 designation. While exact production numbers still are elusive, records suggest that Erich Heuer Karosseriefabrik of Wieden-Ullersricht, near Nürnberg, which had taken over Gläserkarosserie and moved it out of Dresden in 1945, assembled some 17 bodies in three series during the fall of 1952 and winter of 1953. (Heuer already was manufacturing Cabriolet bodies for Porsche and was well known and respected.) Hoffman and Von Neumann recognized that American buyers preferred model names to numbers in those days, christened the handsome two-seater America Roadster.

Von Neumann was Hoffman’s most voracious customer because sports car racing had taken on something of an “on any weekend” fascination. As the accompanying story explains, racetracks – on armed forces bases, in county parks, and closed racing circuits – emerged all over California. Heuer’s first eight cars came to the States with minimal interiors and weighed something around 1,375 pounds. But the body design – with a single grille on the engine deck lid – trapped engine heat and the cars proved to be poor racers that sold for a high price, around $4,500 in 1952. The second series cars arrived with twin grilles but slightly nicer interiors and weighed around 1,500 pounds. Through Hoffman, Von Neumann ordered one final Roadster. Heuer had gone bankrupt completing his orders for Porsche and so Porsche used Drauz Karosseriewerke, a body maker with a robust commercial vehicle fabrication business in nearby Heilbronn to complete this last order.

Von Neumann, in an interview in his Palm Springs home in 1991, recalled his idea: “A prototype, unpainted, shipped to me,” he said. “Don’t paint it. I’m going to modify it anyway. Ship it to me in primer. Don’t put upholstery in because I’m going to rip it out. I want a car to race to win.” Von Neumann handed the car over to his primary dealer Jack McAfee, a well-known racer. McAfee did just that, teaching other Californians in bigger faster cars that this little roadster had capabilities they hadn’t imagined. In a separate interview around the same time, McAfee explained.

“That America Roadster, it was the beginning of the competition car for Porsche,” he said. “All aluminum. Thing only weighed about 1,300 pounds. And it had the first real set of brakes on a car that I ever drove…. You could out-brake anything on the road with that car. And out-handle!”

McAfee had founded his reputation driving “sprinters,” open-wheel single-seaters on fairground dirt ovals. “The thing that upset everybody was the swinging axle suspension in the rear. When you came off the gas, the rear just got light in back. It was very scary. ‘Jeez! I lost it!’ That’s what you’d think.

“I adapted to it. Because I ran the sprinters so long and throwing the car [sideways] – using the car to scrape off the speed, I got right into this Porsche thing real easy.” Class wins and – in some smaller class races, outright victories – piled up trophies on McAfee’s mantle and more car orders for Von Neumann’s enterprise. And all of it kept Von Neumann thinking.

“I think, years later now, that the Roadster America, this little Johnny von Neumann special, was a prototype really for the Speedster,” McAfee reflected. “Von Neumann, through Hoffman, complained that they needed something for a price for the American market. I think these last America Roadsters were a mock up for the Speedster.”

Two years later, Porsche gave birth to the offspring of this idea. Even without DNA testing, its parents were well known: Von Neumann had pushed Hoffman hard for a simple open $3,000 car. Also designated the Typ 540, the Typ 356 Speedster appeared in late 1954 as a 1955 model, with body design by Gerhard Schröder, a mid-1954 arrival who had done numerous convertibles and cabriolets for Swiss coachbuilder Ramseier and German body maker Karmann before joining Erwin Komenda’s staff. Heinrich Klie modeled the new car, derived by modifying and lowering elements of the 356 Cabriolet. Another newcomer, engineer Ernst Fuhrmann contributed twin-cam cylinder heads and then an entire engine series named Carrera. Over time, the Carrera Typ 547 engines mated with 356 Speedster bodies became the weapons of choice in any racetrack battle for the checkered flag.