Want to go 200 mph? Call 911.

That’s what Tom Woodford of California feels like doing after being denied a chance of attaining that magic number at Utah’s Bonneville Speedway for the past two years in a row.

In September 2014, Woodford trailered his newly modified 1975 911 from California to the “World of Speed” event sponsored by the Utah Salt Flats Racing Association (USFRA). That event celebrated 100 years of auto racing on the famed course. Unfortunately, a mechanical issue kept Woodford and his Porsche sidelined, and then this year’s gathering was cancelled.

Even more unfortunate is the cancellation of all other major automotive speed record runs at Bonneville for 2014 and 2015. The Southern California Timing Association (SCTA), had to scrap their August’s “Speed Week” and October’s “World Finals” due to bad weather and disappearing salt. That’s something that hasn’t happened since the ‘90s.

The reality is, with each passing year, it’s becoming more and more difficult for the event organizers to find four miles of hard salt on which to get into the 200 mph club. And you can forget about anyone breaking the 1970 top speed record of 622.4 mph. Bonneville Speedway’s titles of “Fastest Race Track on Earth” and “Land Speed Capitol of the World” are in danger of consignment to the history books.

The Results of Weather and Industry

What’s the reason for this change? Experts say that recent wet weather and long-term federally leased salt brine mining are the two leading causes for the shrinkage of the Bonneville Salt Flats (BSF).

Despite the U.S. Bureau of Land Management’s (BLM) continuous management of the BSF since 1974, sixty-five years of potash mining have taken its toll. Every winter, a private plant on the other side of I-80 near Wendover, Utah, siphons off more than a million gallons of brine from the flats and places it into large ponds where it harvests potash, a potassium chloride rich mineral, for use in fertilizer.

The Bonneville racing community began raising concerns to the BLM about this deterioration as early as the 1960s. But it wasn’t until 1997 that the plant instituted a replenishment plan for the flat’s critical brine aquifer. A net-positive amount has reportedly gone back into the flats over the past dozen years, but many say it’s not enough to make up for the 50-70 million tons of salt that’s already been removed.

Older racers have watched as the “the flats” have gone from thirteen miles and five feet thick to less than three miles long and one foot thick. This seems especially poignant when you consider that the flats were formed more than 17,000 years ago and are an international landmark that has been listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places since 1975.

Speed and the cars are certainly Bonneville’s main draw. But there are other gems to discover, revealed when attending the 2014 event with Woodford – like the amazing lunar-like scenery and the fascinating people who attend. Much like Pikes Peak Hill Climb, the Indy 500, and F1’s Monte Carlo, Bonneville is on the bucket list of many a motorsports enthusiast.

Woodford, age 69, completed his custom 911 streamliner in 2014 to check Bonneville off his list. He’s now very concerned that he may never reach his goal. That would be a shame because he’s spent countless hours wrenching on his one-of-a-kind Porsche.

About the same time that Woodford’s friend and Porsche fixture Dave Aase passed away in 2011, Woodford hatched his plan to achieve his dream of going twice the legal speed limit. “I bought a ‘75 and a rust bucket ‘71E both for $5,000. So I parted the E out to help fund this Bonneville build,” he recalls.

The resulting 1975 U.S. Porsche Carrera 911 was built strictly to the SCTA rulebook. The specific model year was chosen because it has the most aerodynamic shape. The ‘75 Carrera is a narrow bodied 911 with no flares, a front spoiler, and an optional one-year-only single vent flat rear tail.

Everything is Different for the Salt

“Forget everything you know about traditional Porsche racing,” Woodford proclaims. “Weight is your friend on the flats. You need mass to keep the car planted and for gaining momentum throughout your run.”

To that end, Woodford added 250 pounds of ballast to the front end. He welded a half-inch steel plate under the Kirkey race seat that is set as low as it can go. He added 48 pounds of ballast to the steel 15-inch spare wheel that he welded shut. And there’s another 90 pounds of iron he attached to the front pan. He uses two 42-pound batteries in parallel. A sheet of 1/8-inch steel under the front belly pan improves aerodynamics.

SCTA’s classification for this vehicle is F/CBGC. The ‘F/’ designation indicates a 3-liter motor. ‘C’ stands for the classic category (cars produced before 1981). ‘B’ means blown. An engine swap from 2.7 to 3.0-liter puts Woodford’s production 911 in the ‘GS’ Gas Coupe class. Only carbs or MFI are allowed for fuel delivery, but a front air dam, splitter, and parachute can be mounted.

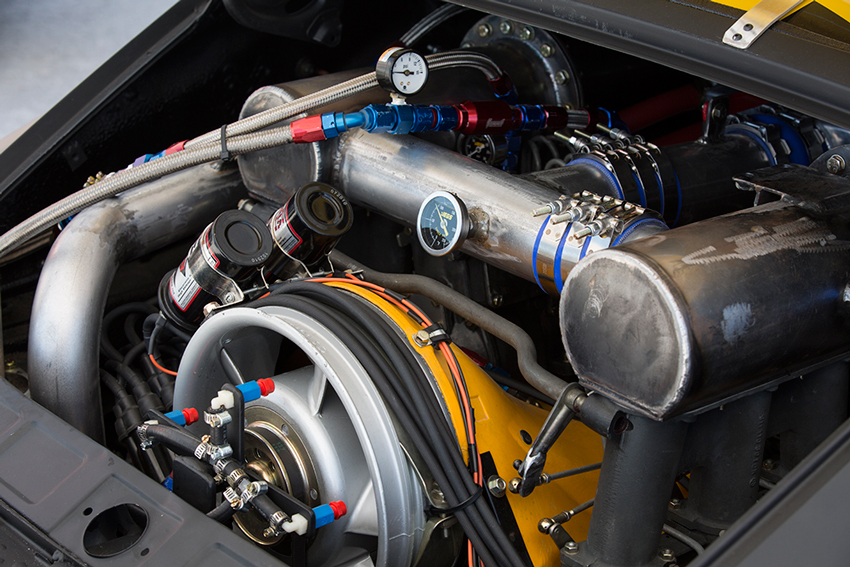

A single water-to-air Porsche intercooler helps produce a claimed 455 foot-pounds of torque from the beefy three-liter turbocharged motor. There’s a Jarvis Tech twin-plug distributor and a remotely controlled mister pointing straight at the air-cooled housing. Woodford uses a five-blade cooling fan because it spins faster. The only engine cooler is a 28-tube unit that is less likely to jam up with salt.

An early 930 4-speed transmission is good for 800 hp and is geared tall enough. Elephant Racing replaced the entire suspension so it would be very firm on the salt. Along with coil-overs in the rear, Woodford installed 22/30 torsion bars. Brakes are stock Carrera from 1984-89. Tarret sway bars and revalved Bilstein shocks round things out.

Narrow Eagle Goodyear tires, sourced from the front of a dragster, prevent floating on the salt. Overall diameters are 28 inches in the rear and 26 in the front. The custom wheels are 15×4.5-inch hub centric steel type, welded 360 degrees around. One-inch lug nuts meet the rules. ‘Moon’ covers complete the streamliner look.

The Porsche’s graphics look plenty purposeful too. Yellow and red decals contrast with the flat black paint. Contemporary 911 ‘Signal Stripes’ on the hood add to that message. All windows are riveted and reinforced Plexiglas, except for a glass windshield and metal rear window. Aase’s name is on the roof and The Eagles lyrics; “Take it to the limit one more time” adorn a side window.

Interestingly, the rules stipulate that the car must retain its rain gutters, and the headlights have to be there too, although they don’t have to work. The bumpers cannot be changed from their stock location, and competitors can’t tape anything up to make the car more aerodynamic.

Inside the trunk and cabin, this 911 looks like a space shuttle. There’s a cool system for the motor and the pilot. A GPS speedometer, voltmeter, boost dial, and air/fuel mixture gauge join the usual indicators, including a big red warning light. Two ten-pound fire extinguishers cover the engine compartment and cabin. Woodford had an Autopower roll cage extensively modified and welded to the braced floor.

Waiting to Exhale

Now that the car is built and the mechanical issues fixed, Woodford is just waiting to exhale, “Everything on this car has a reason behind it. First it needed to pass tech, secondly it needed to go fast. The record for my class is 173 mph. I want to go 200.”

But making it into the 200 mph club seems somewhat less important to him now, especially when there’s a chance there will be no speed racing at Bonneville for future generations. “It’s been projected that if we don’t do something, the salt flat will be a mud flat in 20 years,” Maggie Wyatt has stated. She served as a Resource Area Manager for the BLM from 1994-1996.

In response, a number of prominent groups formed the nonprofit organization ‘Save the Salt Coalition’ in 2011. Team members are currently working with state government officials from Utah and Nevada, along with members of Congress, the BLM, and numerous engineers and geologists to come up with a solution.

For motorsports enthusiasts worldwide, Bonneville is hallowed ground. Unfortunately, it’s ground that is going away. The question, if it were put to a vote, is: More fertilizer production from the Wendover plant, or the ability to have speed racing on a 12-mile long course that has more records than anywhere else on earth? It’s clear how most enthusiasts might vote. Including the late Dave Aase.

Story and photos © 2015 Randy Wells. All Rights Reserved.